Scarlet

Me Somewhere Else, 2018 © Chiharu Shiota

“When my feet touch the earth, I feel connected to the world, to the universe that is spread like a net of human connections,” said the artist Chiharu Shiota, describing her expansive, site-specific installation, Me Somewhere Else, held at Blain|Southern, London in January 2019. Standing in front of this powerful piece, I was transfixed. The Osaka-born artist fills empty spaces with vivid scarlet yarn, in a distinctive triangular schematic; Me Somewhere Else featured an otherworldly lattice delicately touching ghost-white feet, defining how consciousness spreads beyond the tangible, the way arteries spread through a body. Shiota’s work features immersive, networked environments spun out of yarn, often tangled with vehicles like boats, or used possessions, haunted with memories. Her work is imbued with a longing for her motherland and the loss of her future life blood through ovarian cancer. My mother also had cancer and I immediately understood that feeling: when you are willing every cell in your body to win its war against the disease.

Shiota works in scarlet more than any other colour, and for good reason: it’s a hue that has an extraordinary resonance. In the western world its deep religious associations are entwined with displays of power and wealth. In China the colour represents happiness and good luck, and today, Chinese New Year, you’ll see an explosion of scarlet and gold throughout the country and enclaves around the world: exuberant dragon dances ushering in joy, peace and prosperity for the coming year. In Japan it is the hue of life: the scarlet double-T torii (gates) at the threshold of Shinto shrines ward off demons. It is also a red that signals danger, anger and of course, passion. It’s fascinating that one shade of red should carry the weight of so many – and contradictory – signals. It is laden with symbolism: from the umbilical cord at birth and the neural pathways in the human brain, to the familial and cultural connections that bind us together, scarlet is the colour of life: the colour of blood.

Blood cells are made from protein, iron and oxygen. Within red each cell is a protein called haemoglobin, with sub-units called hemes which bind oxygen with iron. So, the more we inhale, the more oxygen mixes with iron and the brighter our blood becomes. This mixing of elements is the very core of our existence. Derek Jarman, diagnosed with HIV, wrote Chroma the year before he died in 1995. I think that perhaps when you explore the prospect of imminent death, you feel more fully alive. With his own senses about to be extinguished, he tried to capture the essence of this experience.

“Each victory of the red cells brings death…for the virus is red. The dance of death. Red plague cross. Red as scarlet fever – the small pox. Red has always embraced the hospital. The tenth-century physician, Avicenna, dressed his patients in red clothes. Red wool tied around the neck protected. Like for like. Colour for cure. Red moved the blood. Avicenna made medicine from red flowers. If one gazed intently at red the blood would flow……RedStopRedStopRedStop”

Chroma, Derek Jarman.

Vintage Classics 1995. ISBN: 9780099474913

Iron is the heart of our existence on a planetary level too: Earth’s core is a solid ball of iron, giving us magnetic poles and the ability to navigate. Thanks to iron, humans could explore and, crucially, get back home again. Mars has so much iron oxide – the same compound as our blood – that it appears as a rusty-red. As if to make this connection very clear, the first lunar eclipse of the year rose low on the horizon, cloaked in scarlet. This ‘Super Blood Wolf Moon’ was caused by the moon’s unusual proximity with the earth. In passing through earth’s shadow, our planetary companion acquired its reddish tint and for a moment, all of us were linked in wonder.

Blood Wolf Moon, 2019 © Andrea Hamilton

Scarlet is central to the Judeo-Christian story: the colour of sacrifice and atonement, of Christ’s blood. In 1464 Pope Paul II decreed that all his cardinals wear robes of scarlet, as they do to this day, both a reminder of Christ’s sacrifice but also a display of power and wealth. Scarlet dye was achingly expensive – in fact the word scarlet comes from the Arabic siklāt, meaning cloth dyed red. The original scarlet dye came from a tiny grub-like insect called kermes ilices, known in biblical times as the crimson worm: 80 kermes were needed for just one gram of dye. The insect’s fascinating life cycle is central to the faith: it parallels the Passion of the Christ, life out of sacrifice. When the female comes to lay her eggs, she forms her body into a hard shell around them and attaches herself to a branch. So firmly attached is she in fact, that this is her last act. The moment of birth is the moment of her death: as the newly-hatched kermes emerge from her shell/body, they are coloured red by her self-sacrificed remains and remain so for the rest of their lives, wearing their bloodline like a cloak. In the last, as her body disintegrates, the waxy white shells fall from the tree, leaving a snowy, woollen effect around the evergreen oak, like little sins forgiven. It’s beautifully illustrated in Isaiah 1.18:

‘…though your sins are like scarlet,

they shall be as white as snow;

though they are red like crimson,

they shall become like wool.’

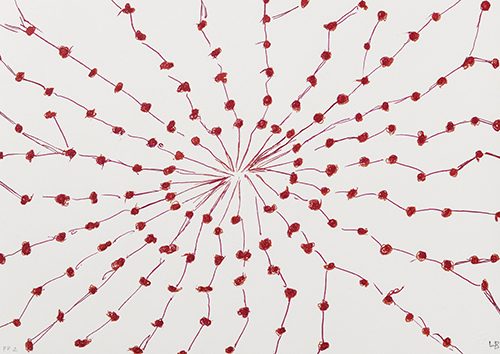

Repairs in the Sky, no. 3 of 9, from the series What Is the Shape of This Problem?, 1999.

Louse Bourgeois © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY.

If scarlet represents the Passion of the Christ and the blood of martyrs, one of the strangest contradictions is that it is also the colour of lust and adultery – the scarlet woman. This was fictionalised in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s masterwork, The Scarlet Letter. Written in 1850, and set in a 17th century Puritan Massachusetts Bay colony, it tells the story of Hester Prynne who conceives a daughter, though her husband is presumed dead, and for this shame she is required to wear a scarlet ‘A’ (for adulteress) on her dress. Hester’s innocent daughter Pearl is also stigmatised, which becomes the central question: how one can create a new life of repentance and dignity? It examines the notion of redemption – both personal and societal.

The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1850.

Enhanced Media Publishing, 2017. ISBN: 9781387064564

Even in this day and age, wearing scarlet as a woman is to make a striking statement about sexuality and desire. Statistically, waitresses who wear red get more tips: a smear of Chanel’s Rouge Allure lipstick is a come-hither – and Jessica Rabbit’s scarlet dress, split to the thigh, a walking promise. As Derek Jarman wrote in Chroma, “Red protects itself. No colour is as territorial. It stakes a claim, is on alert against the spectrum”. It all comes back to the power of blood – that is the sensual promise of red after all, that a woman is sexually mature. Yet our relationship to the hue is mediated and controlled: women must not be flowing, open hearted, and passionate, to only ever allude to the workings of the body.

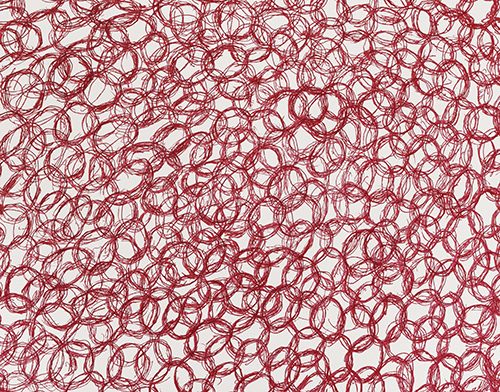

To Unravel a Torment You Must Begin Somewhere, no. 8 of 9, from the series What Is the Shape of This Problem?, 1999. Louise Bourgeois © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY.

For artists like Frida Kahlo and Louise Bourgeois, the use of blood red is empowering. Known for her exploratory, sexually explicit works, Kahlo’s cathartic response to finding her lover Diego Rivera in bed with her sister was to paint a riotous bloody scene, red paint spattered garishly all over the frame. Bourgeois painted whole rooms with it, sewed stories with it, and then made a lullaby out of red. Red is affirmation at any cost, it rises above the danger or contradiction of fighting for what we love.

Scarlet Sea, 2012 © Andrea Hamilton

In the end, scarlet is most truly the colour of joy – of being alive, of the rich panoply of human existence, from sacrifice to passion, from anger to love. As fashion designer Valentino said, “Red has guts… deep, strong, dramatic. A Goya red… to be used like gold for furnishing a house, it is strong like black or white.” My meditations on scarlet led from a surreal dawn on 11 April, 2012, when after a long exposure I was lucky to capture a mirrored sea and sky of the warmest of light. I thought about how quickly red can be a deep pleasure or a pain, and ringing in my ears from generations of naval DNA was: “Red sky at night sailor’s delight, red sky at morning, sailor’s warning.” If you feel barely alive, listless and rigid – especially in these cold and dark months – harness the power of warm, rich scarlet to bring out your inner warrior. Refuse to be like others driving down the same road, and spring onto your own.

Explore Further:

Exhibitions:

Now until 24 March: Louise Bourgeois, Artist Rooms, Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge.

Now until 20 March: Chiharu Shiota: Lifelines. 100 Jahre Revolution, Berlin 1918/19. Podewil, Berlin.

22 February-27 April: Ken Currie, Red Ground. Flowers Gallery Kingsland Road, London.

16 March-18 August: Anish Kapoor. Pitzhanger Museum & Gallery, London.

11 May-24 November: Melissa McGill, Red Regatta. Venice Biennale, 2019, Venice.

20 June – 27 October: Chiharu Shiota, The Soul Trembles, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo.

Other Projects: Wondrous Strange

Wondrous Strange No. 2 © Andrea Hamilton

“These photographs aim to capture the fragile, the innocent emotions and developing identities of the adolescent models. In a way, they speak about something akin to a delicate but persistent memory that cannot be fully restored. Images that are enigmatic fascinate me, where there is an intriguing, disturbing feeling that reflects life’s challenges. Wondrous Strange’s photographs trigger within us a sense of something irredeemably lost yet still present.”

Colour Combinations: Scarlet/violet

No. 301 (Reds and Violet over Red/Red and Blue over Red) [Red and Blue over Red], 1959.

Mark Rothko. Image © Museum of Contemporary Art.

When I think about rich reds, the combination of scarlet and violet comes to mind, because I see it frequently when gazing out to the sea at sunset. Towards the end of his life, Mark Rothko painted in rich, resonant colours: deep reds, bruised purples, sombre magentas, as if foreshadowing Jarman’s meditation on red at the end of his life. No. 301 [Red and Blue over Red] deep scarlet with a cool band of purple, keys into the beauty of floating fields of pure pigment, and reminds us that how colour is both deeply personal and also a shared experience – colour feeding emotion in the purest way.