THE MANY WAYS WE SEE OCEAN COLOUR

Nico Kos Earle

Independent curator, Creative director, Freelance writer

“The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.”

– Aristotle

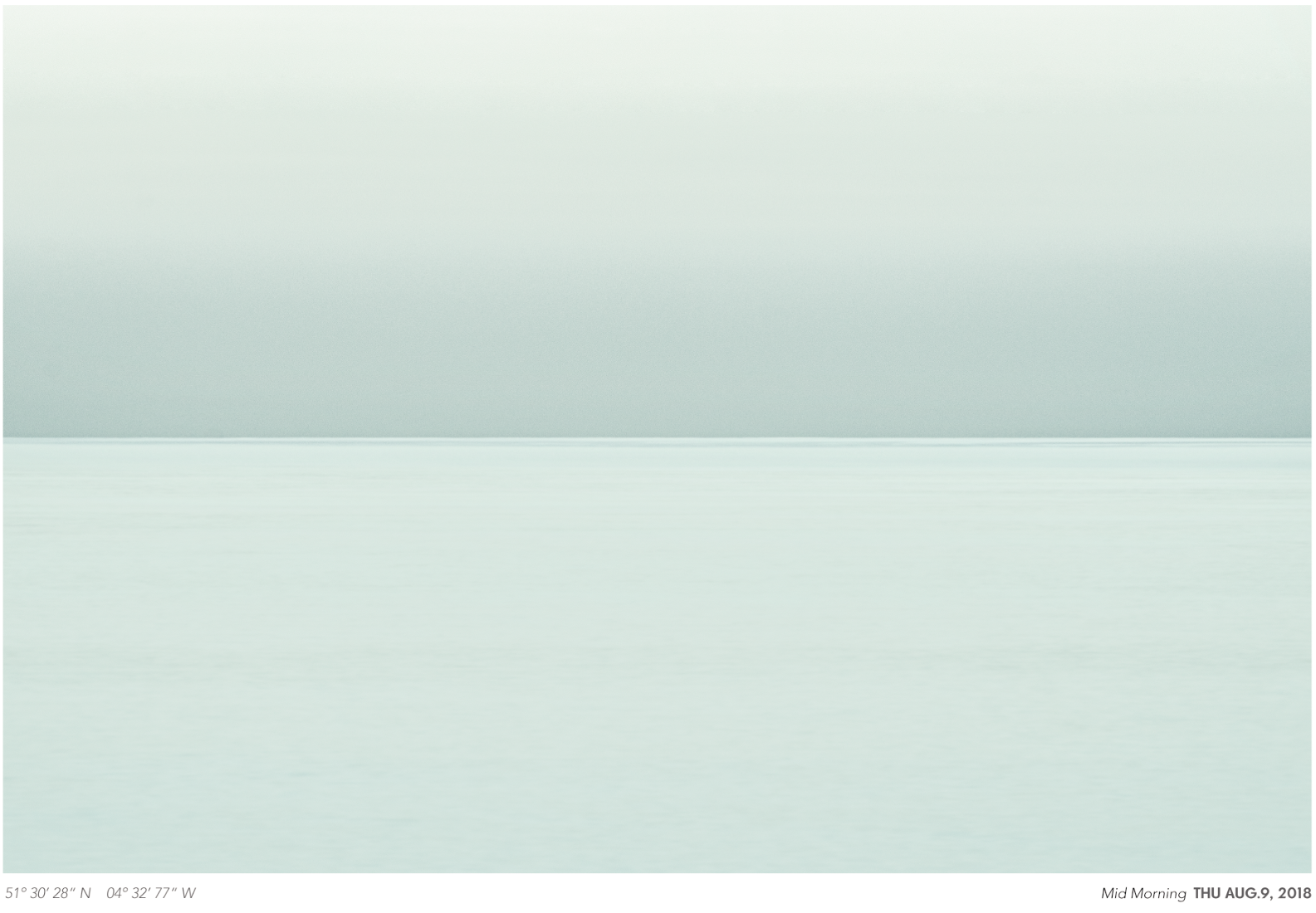

Looking at something repeatedly and intently does not necessarily lead to a complete understanding; more often, it opens your mind to the infinite depth of potential knowledge. Consider Andrea Hamilton’s Sea Chroma Library, an expanding archive of seascapes all taken at the same place, over two decades. In Early morning, Saturday, April 12, 2014, the slate-dark sea is agitated; waves clash in short strokes of light and shadow, and the sky responds with the tender apricot bloom of a rising sun… In Midday, Sunday 10 of August, 2014, the ocean is a bicoloured sapphire of phthalo blue and icy turquoise, a sky within the sea, under a cerulean sky… Early morning, Saturday August 1, 2020, we see sea mirroring sky in a smooth, harmonious indigo, separated only by the clean white horizon line.

With such variety of colour, it is hard to imagine these images are all from one place. Somehow, they seem to say, “The more you know, the less you know”. This statement is attributed to Aristotle, whose teacher, Plato, argued that all things have a universal form, and that some universal forms exist independently of particular things. Aristotle disagreed with Plato on this point, arguing that all universals (katholou) belong within the thing itself. Aristotle believed that, ‘to experience is to learn’, and with regards to the ocean, close observation will teach you that it is unpredictable. Only with patience and time, like The Old Man and the Sea, can you begin to read its endlessly mutable surface.

This multivalency is also a characteristic of the way water holds and shows colour. We may carry an image in our mind of a blue ocean, but when we stop to look at it, we cannot pin its universal colour down. That is because it is both its own colour, and a reflection of the environment. On a perfectly calm day, the ocean becomes a mirror to the sky. Beneath its glassy surface hides a universe saturated in blue. It seems to follow then, that because it acts as a mirror (not entirely false) that reflects the blue sky, the ocean is blue (not entirely true).

Unlike earthly pigments, which interact with lightwaves by absorbing some and reflecting others, the colour of water is the phenomenon of vibrational transitions rather than an interaction of visible light with a substance’s electrons. Known as Rayleigh scattering (which is also why the sky is blue), the deeper the water, the more saturated its hue, as blue light waves are scattered over a greater volume. This is why small rivers and lakes aren’t as blue as the ocean. And, as the weather shifts, so too does the palette of a seascape; colour appears and dissolves in an endless ebb and flow.

For the artist Andrea Hamilton, the study of ocean colour has led her in multiple, overlapping, and interrelated directions from the science of perception and history of colour through to a notion of the sublime in art. In pointing her lens at this mirrored surface, she is not only asking, “How many colours will I find?”, but also, “What is my capacity for seeing colour, and does this reflect how I see myself?”. Like the architect Keller Easterling suggests in her book Extrastatecraft (2014), much of the world can only be apprehended as if, “Looking at the surface of water”.

Deep, complex and boundlessly fluid, water is a potent motif in contemporary art, and an essential component in the creation of images, in particular photography. Zoom out from one location, and we know that chromatic changes proliferate across the many oceans that cover 70% of this planet. Where there is Caribbean sun, we see a warm paradise encapsulated in the turquoise waters, while the icy winds of the North Sea pound the waves to an inky darkness. But it is simplistic to see the ocean as shades of blue: the ocean’s capacity for colour is infinite. When light waves reach actual waves, the majority are absorbed; but some bounce back and are reflected in the colour we see.

Furthermore, how much light is absorbed depends entirely on what is already dissolved in the ocean. A constant flux of microscopic algae and tiny sediments, known as ‘coloured dissolved organic matter’ (CDOM), alter the ocean’s hue from indigo to sapphire, jade or pine green, through yellow, rust and sometimes red. As the CDOM are absorbed, they transform the water’s colour by interacting with light.

This radiance has also become a vital metric in climate science: just as the ocean absorbs light, it absorbs heat. Satellite observation of ocean colour radiometry involves the detection of spectral variations in the water-leaving radiance (or reflectance); sunlight backscattered out of the ocean after interaction with water and its constituents. Unable to accurately measure ocean temperature, scientists now use equations that relate colour to temperature. Known as the Kelvin scale, ocean colour is also relative to its temperature. Oceanographers like Anand Gnanadesikan at Johns Hopkins University have been using these maps to study the health of phytoplankton: they have found a direct correlation between their life cycle and climate change. As the ocean warms, the ice melts and the seas rise, periling our way of life. (2&3)

Because it is fluid and boundless, water suggests a way of understanding a world that is constantly changing. From this perspective, the colours documented in Hamilton’s library also show us a picture of climate change. As Easterling says, “To survive our rising oceans… we must learn to read water.” Reading water is about being present in the constant flux, but also cherishing moments from this flow that are meaningful – like the individual photographic works from Hamilton’s series We Are The Weather. We begin to see that because everything can be as fluid and mutable as the ocean, we can learn to accept new states of being, and find a way to align ourselves with the moment we find ourselves in.

Nico Kos Earle, 18.02.2021

(edited by Hermione Crawford)

1. The sky is blue not because the atmosphere absorbs the other colours, but because the atmosphere tends to scatter shorter wavelength (blue) light to a greater extent than longer wavelength (red) light. Blue light from the sun is scattered in every direction, much more so than the other colours, so when you look up at the daytime sky you see blue, no matter where you look.

2. In 2011, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) foundation launched TBA21—Academy together with Markus Reymann, a globally dispersed ocean conservancy that ‘deploys artistic discourse as a means to create new knowledge about the water world’ through maritime expeditions across the globe. Central to their mission is to highlight the ecological health of the ocean.

3. One of the expedition leaders is the curator Chus Martínez, head of the Art Institute at the FHNW Academy of Arts and Design in Basel. Inspired by her work with TBA21, she initiated a series of seminars entitled Art Is the Ocean, which examine, “The role of artists in the conception of a new experience of nature”. In her accompanying essay Gathering Sea I Am!, Martínez argues that the ocean, and nature at large, is not only a metaphor for the dissolving axioms of the past century, but a set of, “New conditions of space, politics, action, gender, race and interspecies relations”.