TIME AND WATER

Time and Water can be seen as the first chapter or opening sequence in Colour of Time, which reflects the start of creation. The series borrows its title from the first stanza of Icelandic poet Steinn Steinarr’s famous work from 1948, which left my spine tingling:

Time is like water,

and water is as cold and deep

as consciousness.

And time is like a reflection

made partly by water,

partly by me.

Time and water

rush trackless to vanish

inside my consciousness.

These works present my abiding interest in the thresholds that divide and connect the sea to land or sky: the space between things. I am fascinated with the quality of light and the spatial immensity of the ocean, and have enormous reverence for something so vast, where perspective, scale, time and distance momentarily become intangible, for feeling so small in the presence of something so unquantifiable.

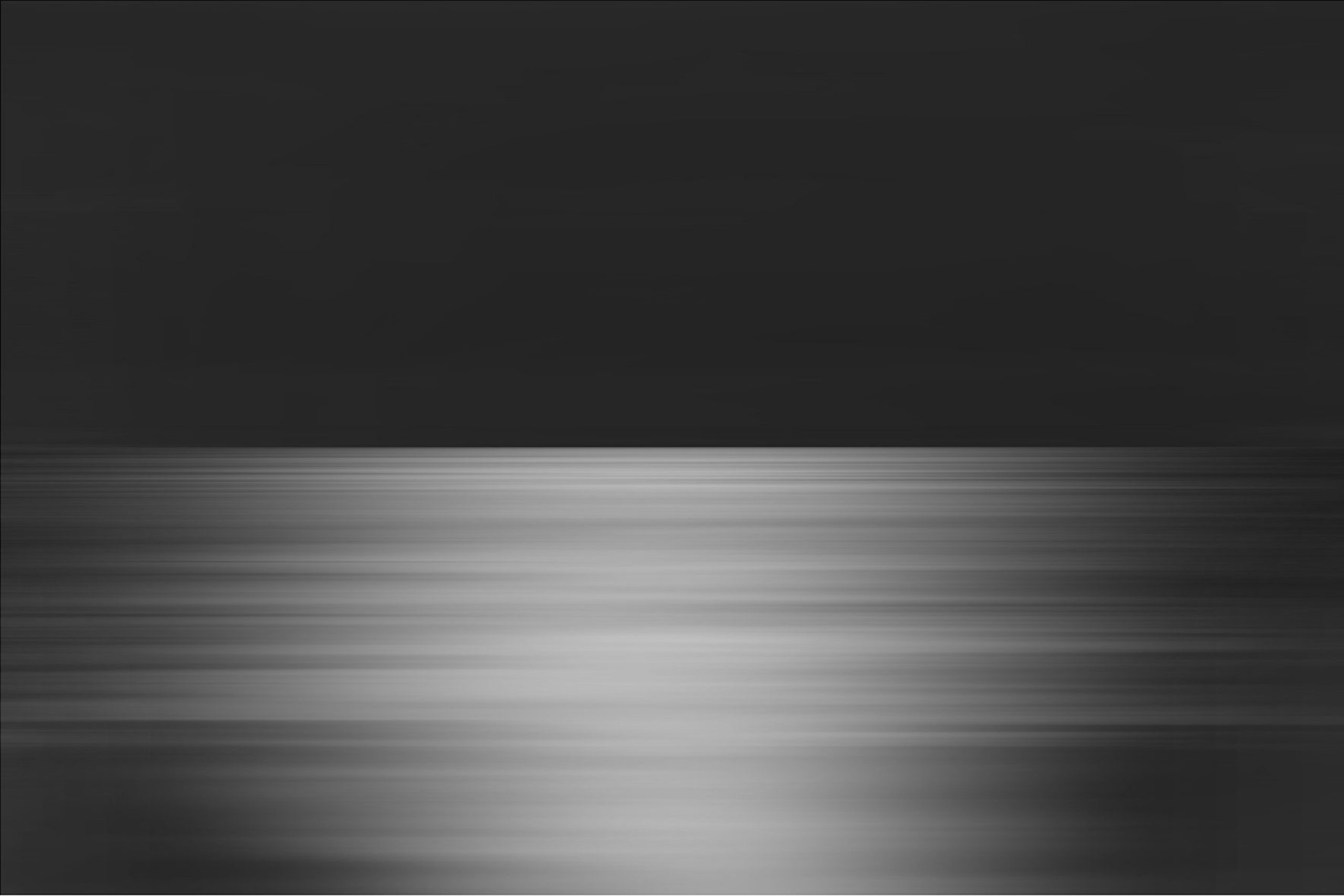

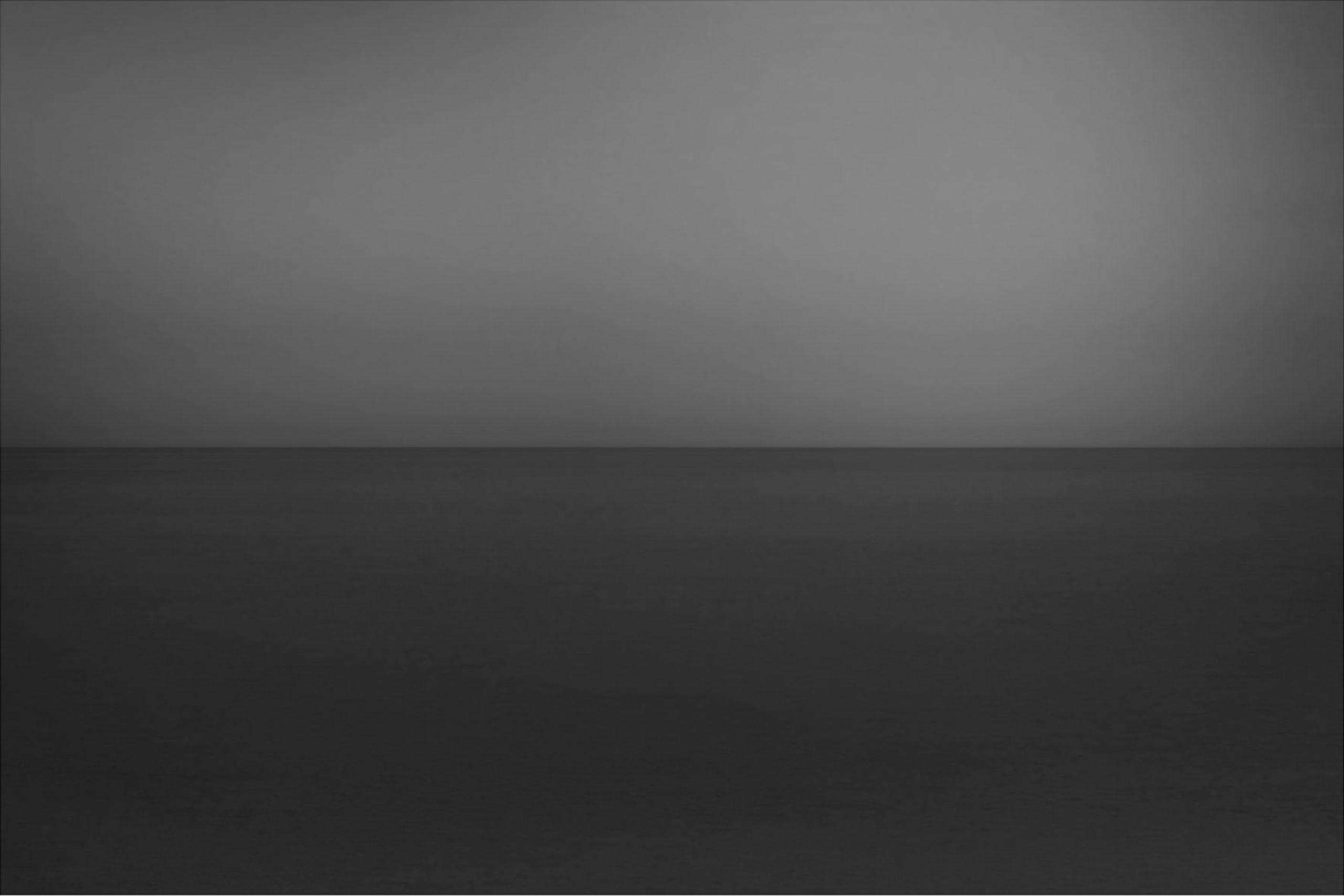

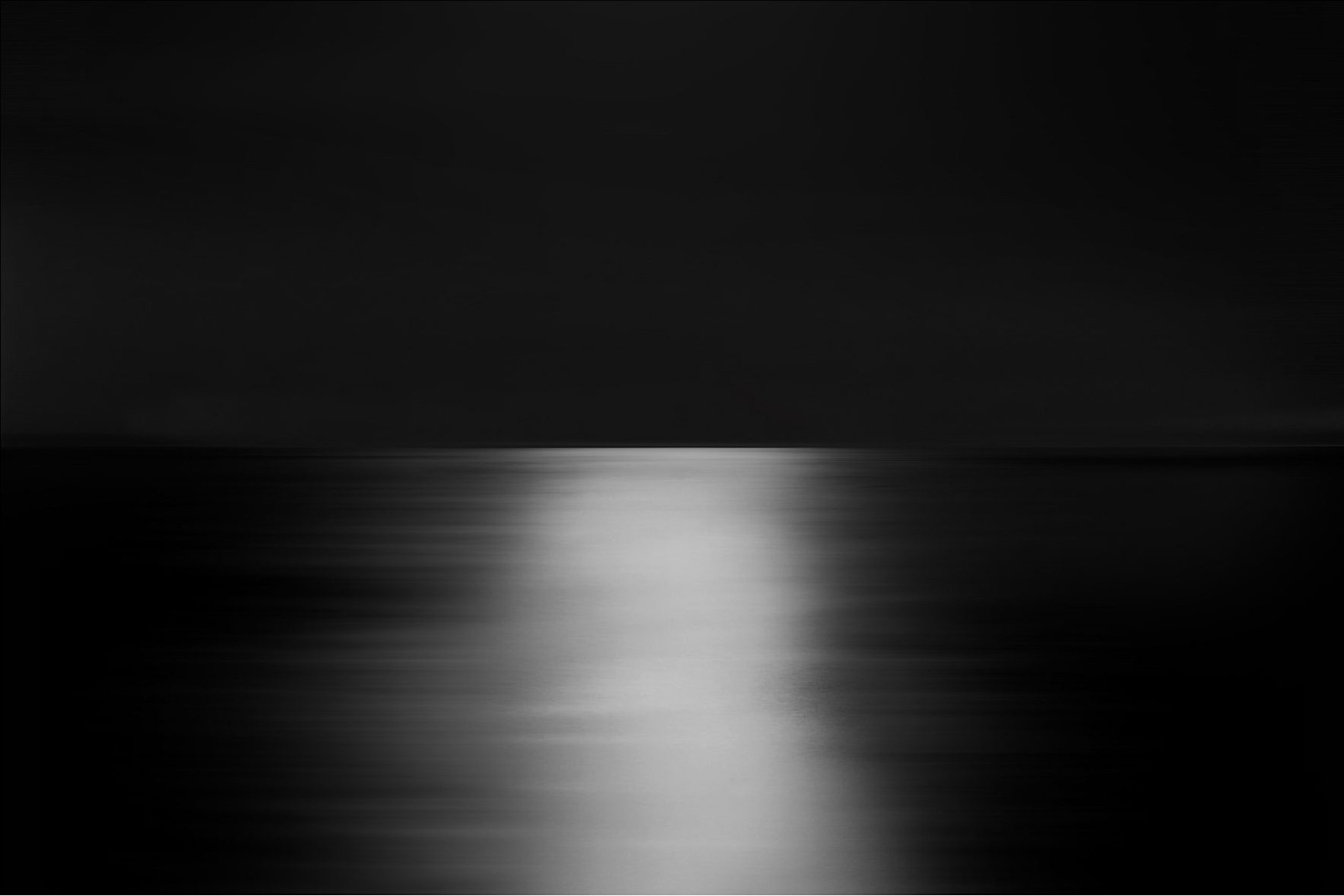

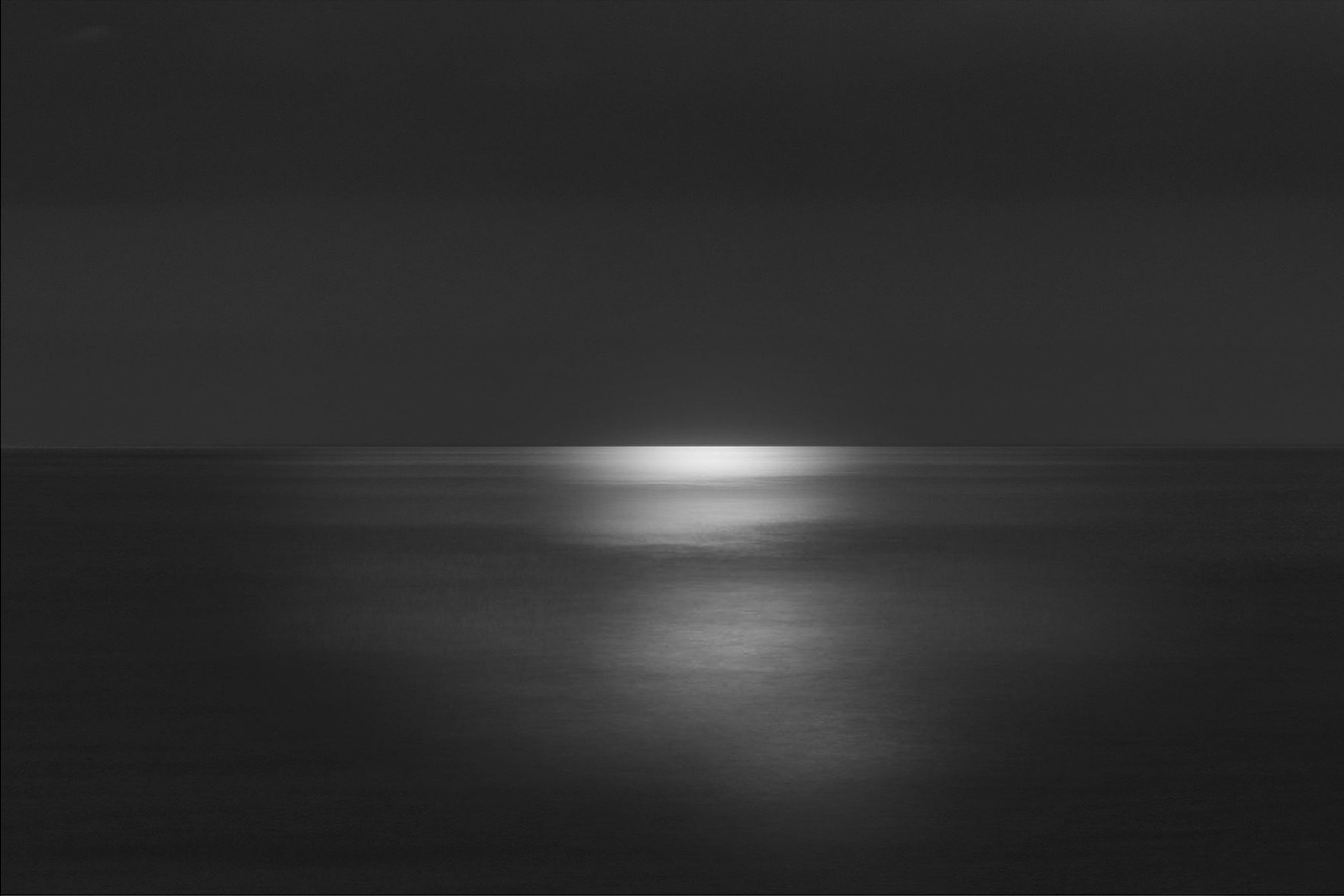

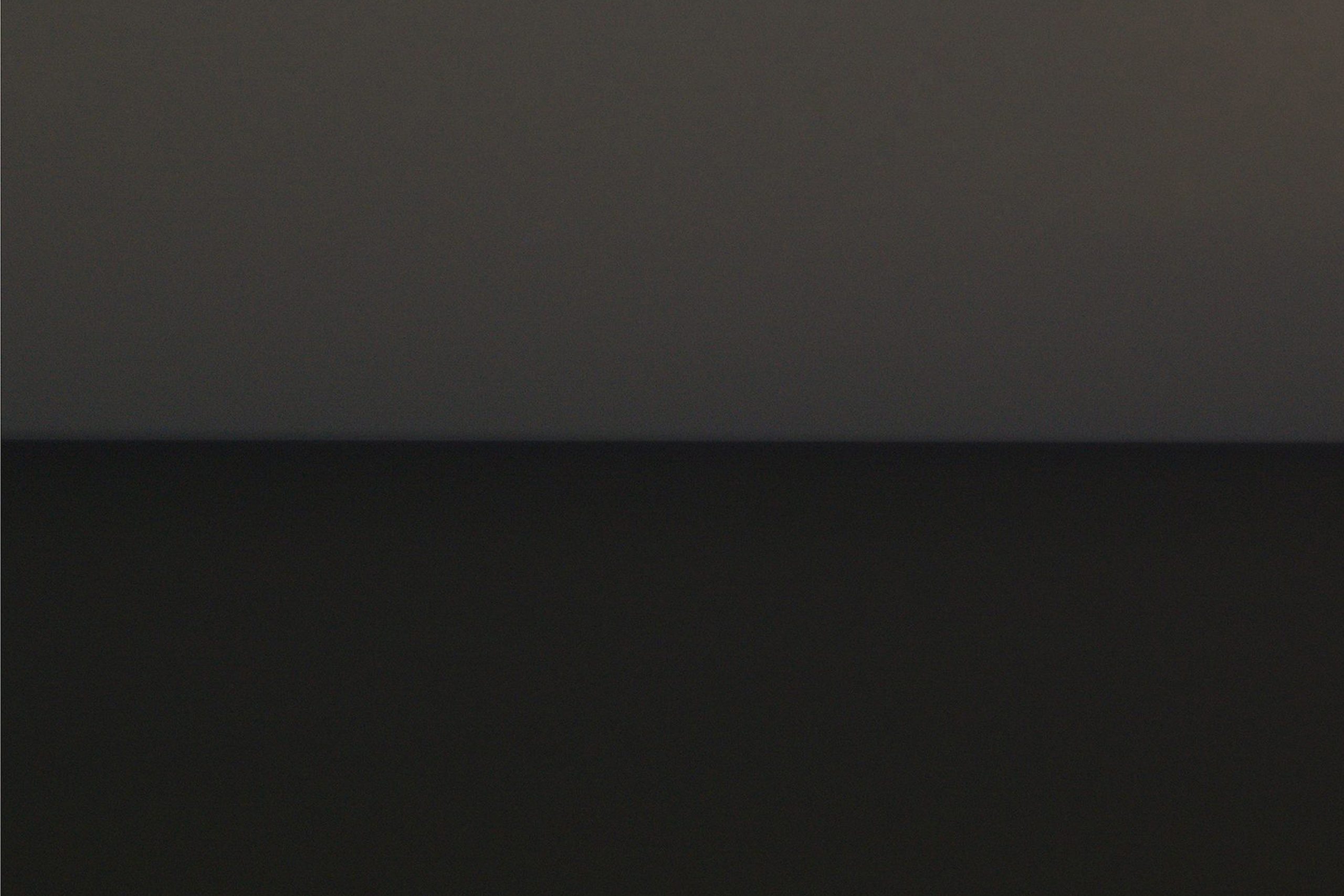

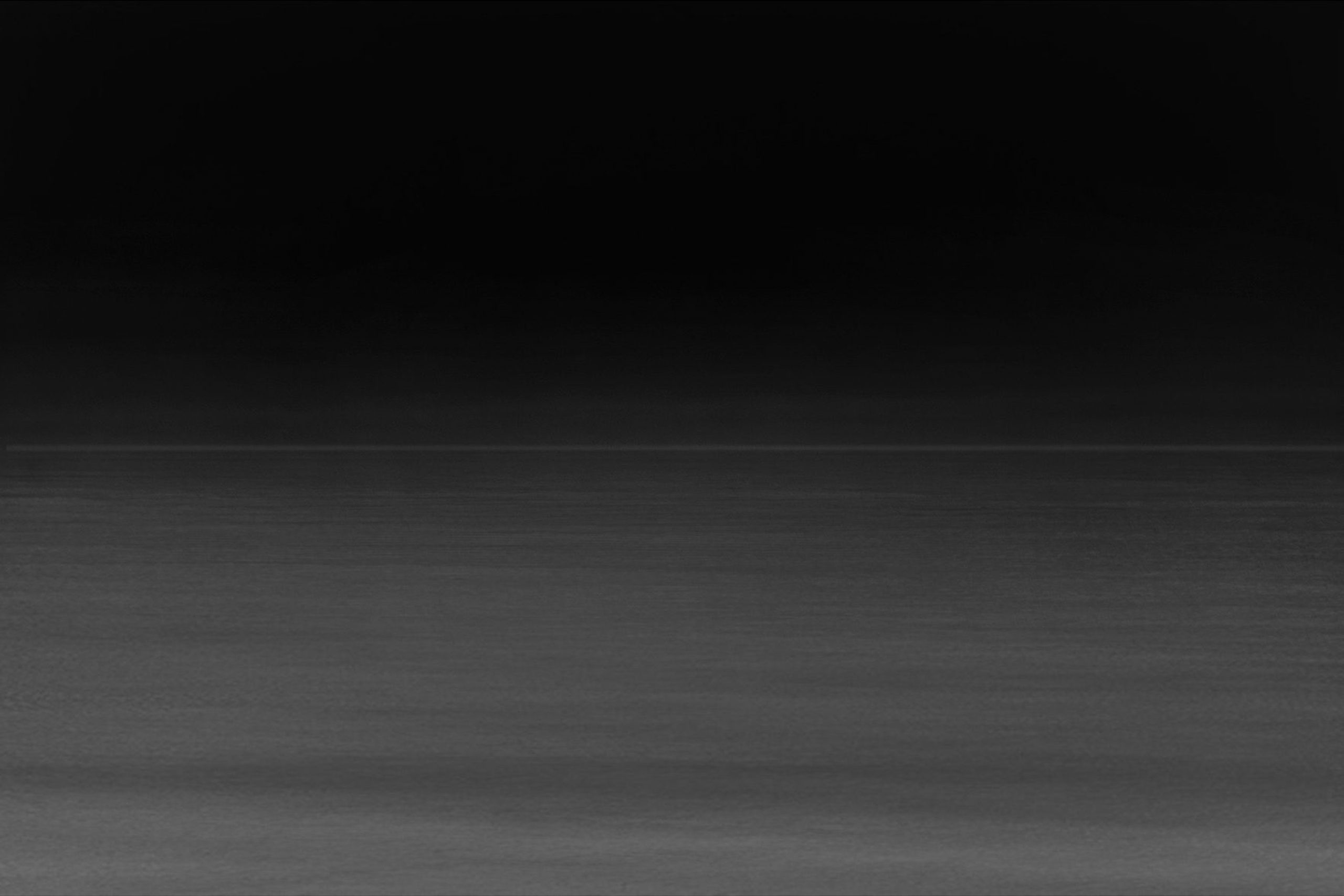

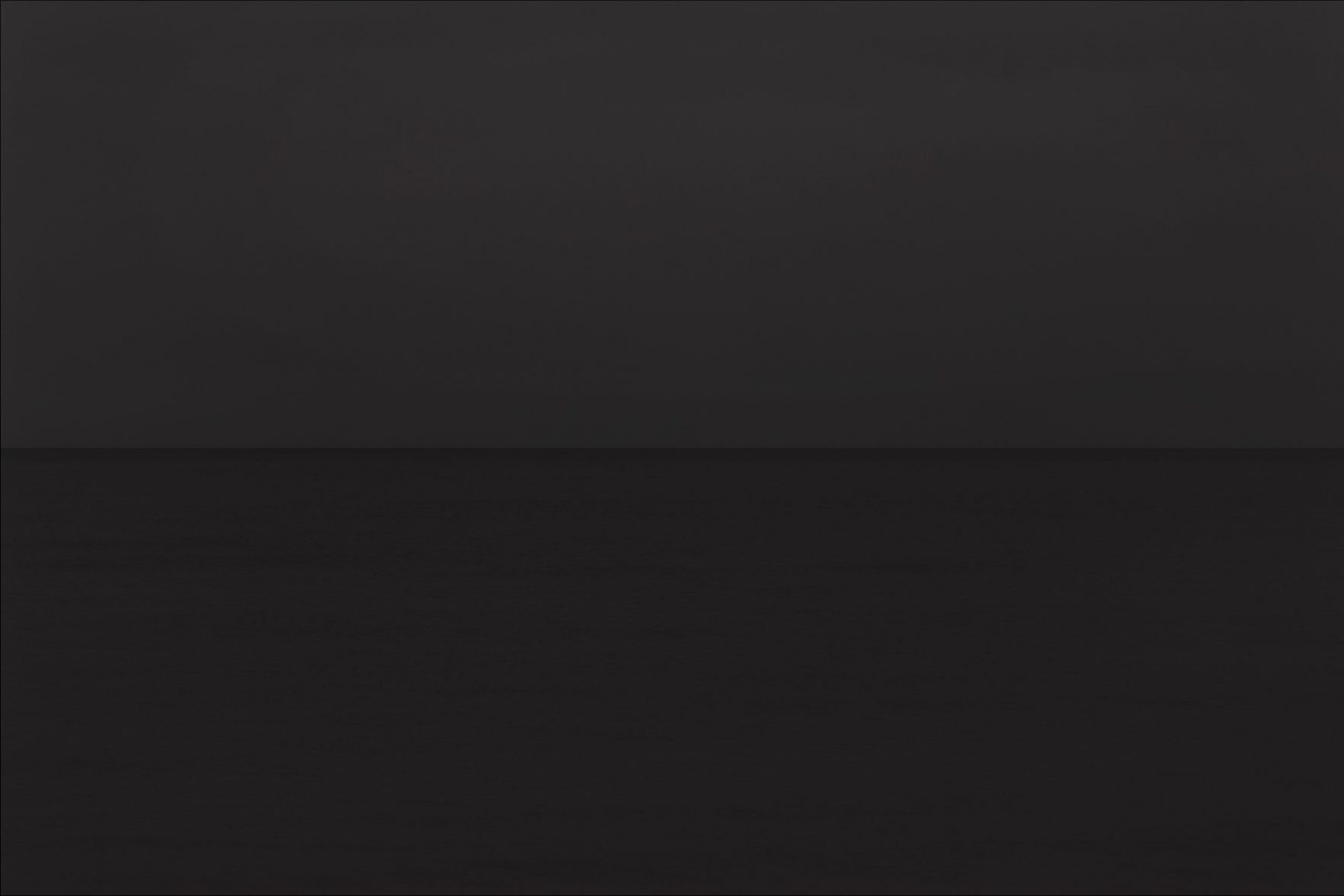

In some ways my work is an attempt at formalising these liminal spaces, and photography is a process of identifying this quality. Exposed under the light of dusk and dawn, the camera shutter is held open for up to fifteen minutes, recording the ocean and sky as it continuously repositions itself on the frame. It is a process both dependent upon and vulnerable to chance, and the resultant image is an accretion of past and present. Each moment is layered over the moment immediately preceding it – a single image that embodies the weight of cumulative time and unending metamorphosis that is the ocean.

The black and white series Time and Water represents the beginning of consciousness, the first light, and the beginning of the life force, of ‘chi’ as it is called in Buddhism. For me, it is a meditation on time, examined through repetition and constancy. Often a soft, opaque mist floods the frame and connects the ocean to the air as it was in the beginning of creation. When I intuit a ghostly feeling from the image, or when it transports me to another place, I like to think that some of these views have remained the same since the beginning of time. After all, we evolved from the sea.

In many ways this project has developed like a natural history collection; I have always collected fossils, and ammonites in particular remind me of our ancestors. This continued observation of the earth’s oceans has led me to researching on a project with NASA scientists, looking for the presence of water on Jupiter’s moons. If they find water, it will likely hold tiny, frozen organisms, which could reveal the beginning of our existence.

My photographs follow the law of series, and the notion of ‘the serial’, capturing the changing mood of nature from a single constant standpoint. This was established as a concept in art history when Claude Monet painted his Haystacks and Rouen Cathedral series. Monet’s identical views depicting one motif in varying light and weather conditions, became one of the triumphs of art. However, Monet was less interested in the motif than in the sudden moment, the shifting sensory impressions and perceptions of the human eye.

Influenced by scientific discoveries and by photographs, Monet tried to record ‘what I sense, I perceive’. The importance of a strict structure and rule with seascapes came to me from Hiroshi Sugimoto, who has travelled the world photographing seascapes from the same vantage point with his 8x10in field camera.

I have also been inspired by the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s series on water towers and the legacy of August Sander, who aimed to photograph all types of German people in a systemic, objective and comprehensive way. The Bechers’ work also resonates with that of the 19th-century photographer Édouard Baldus, who documented French national monuments, and the 20th-century grid presentation of Minimalist artists, for example Carl Andre.

The Time and Water series engages us with repetition on two levels, through representation of the ocean as a rhythmic entity of waves, tides and seasonal changes and also in the repetitive nature of the project, image after image of the same black and white composition, the sky above and the ocean below, the horizon splitting perfectly across the exact middle of the composition. The location always remains the same: our family beach house in Vero Beach, Florida where I have been returning to every year of my life. I am happy there, connected with the sea and the stars and feel thankful that this is enough, and all I really wish for. It allows me to focus on the changing light and atmosphere, the movement of the moon and the tides, the effect of weather, and its effect on me.

Initially, I called this project Sea Studies when I began 20 years ago. It has since been named the Colour of Time, and within this Time and Water represents the beginnings of all beginnings. Where there is only light and dark.

What intrigued me is how these black and white images represent balance, yin and yang, and somehow reflect the dualism that pervades our being. The theory of yin and yang tells us that everything that surrounds us is made up of two opposite forces, that harmoniously unify to favour movement and, in turn, change. So, while yin symbolizes darkness, water, intuition and the ability to nurture life, yang constitutes momentum, luminosity, expansion and fire. This concept, ingrained in Taoism, constitutes in itself a framework of undeniable reflection and, at the same time, wonder. It is like the sky reflected in the sea.

This idea of reflection is central to the series. We are all moved by the sea as if it had some control over our feelings. We are calm when it is. When it is agitated, so are we. Like humans, the ocean has a skin, which contains, hides and sometimes reflects what lies beneath… a mysterious interior terrain. The seabed is not flat, it has a complex geography with its own alps and chasms. Our inner structure is not a domesticated plain. It’s a jagged terrain of memory as deep and unfathomable as the great waters.