WE ARE THE WEATHER

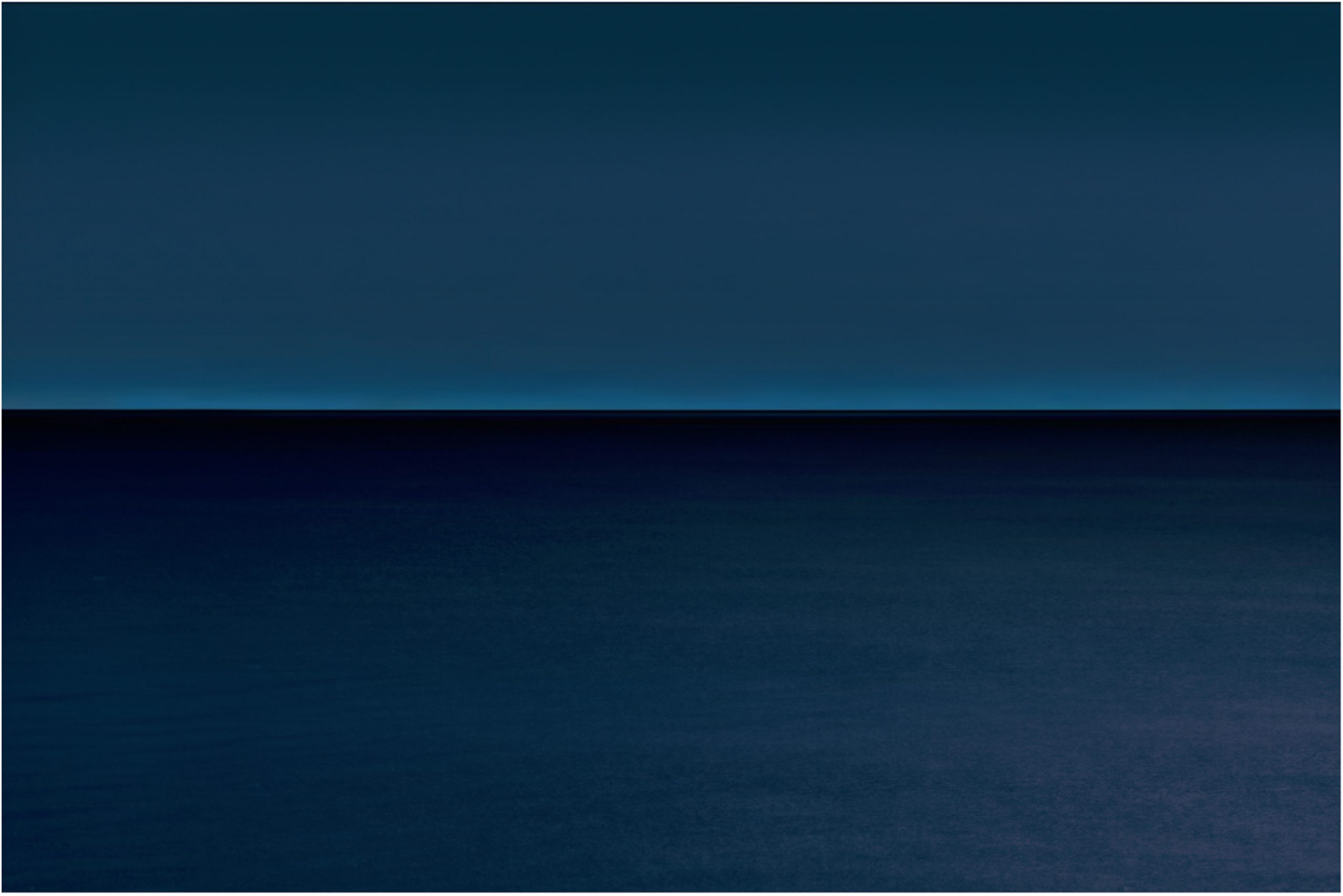

(A photographic series by Andrea Hamilton from Colour of Time)

“As if instinctively our soul is lifted up by the sublime, it takes a proud flight and is filled with joy and vaunting, as though it had itself produced what it heard”.

– Dionysius Cassius Longinus, On the Sublime (Latin: De sublimitate) 1st century AD

This series of works is inspired by Roni Horn’s literary work Saying Water (1999), a sublime, poetic response to the River Thames, infused with epistemological queries. Considering the ‘quilted’, ‘matte’, ‘referential’, ‘indeterminate’, and ‘probing’ aspect of the water’s surface, she explores the breadth and depth of her own emotions. “Watching the water, I am stricken with the vertigo of meaning… When you say water, what do you mean?” Like Andrea Hamilton, Horn is an artist who has dedicated most of her artistic career to the study of water, suggests that this soft, ambiguous and reflective fluid, so vital to our physical make up and existence, has the capacity to mirror our deepest selves. In referencing Horn, Hamilton is both illustrating her response to the flow of ideas, and acknowledging water as a form of perpetual relation in creating art.

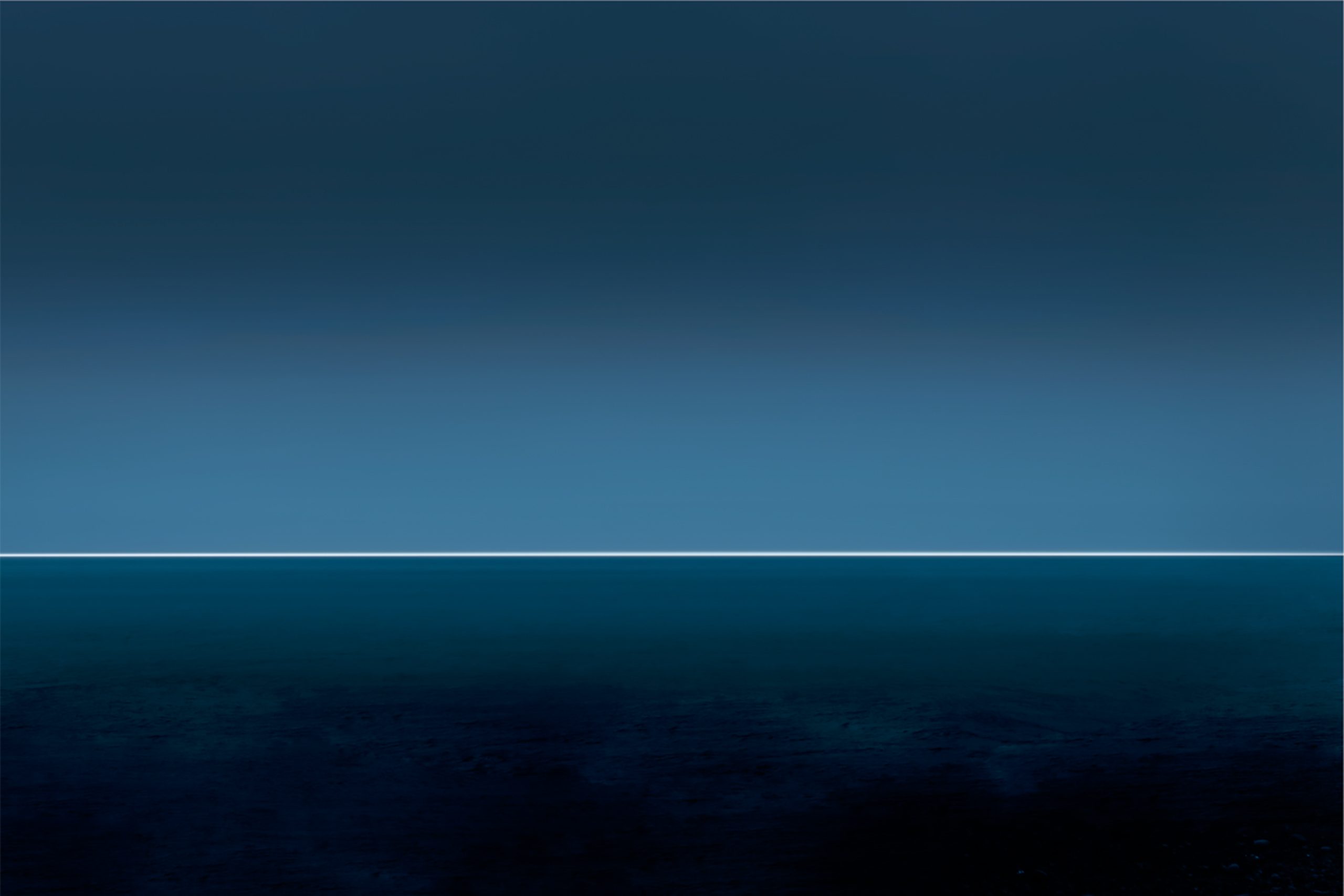

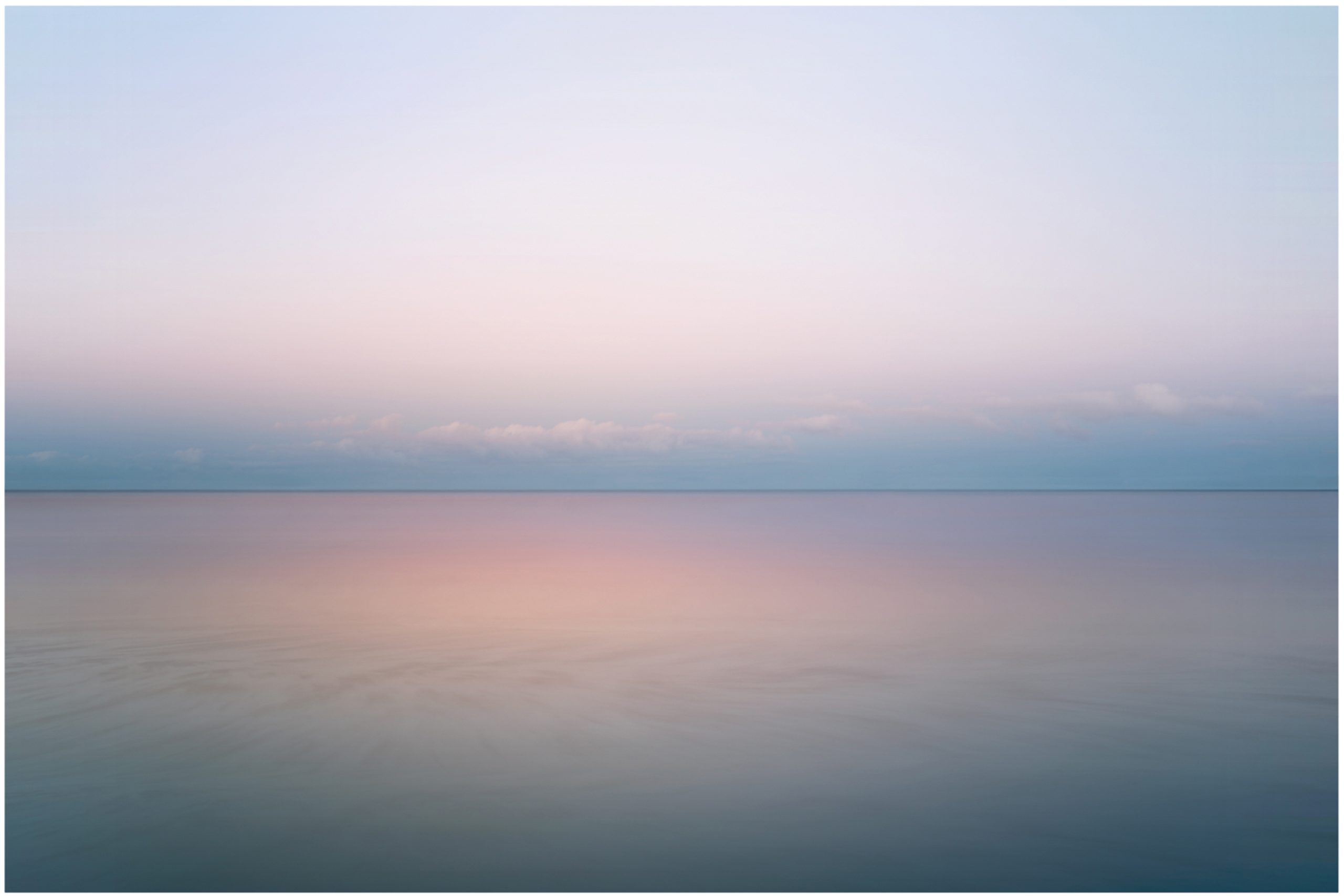

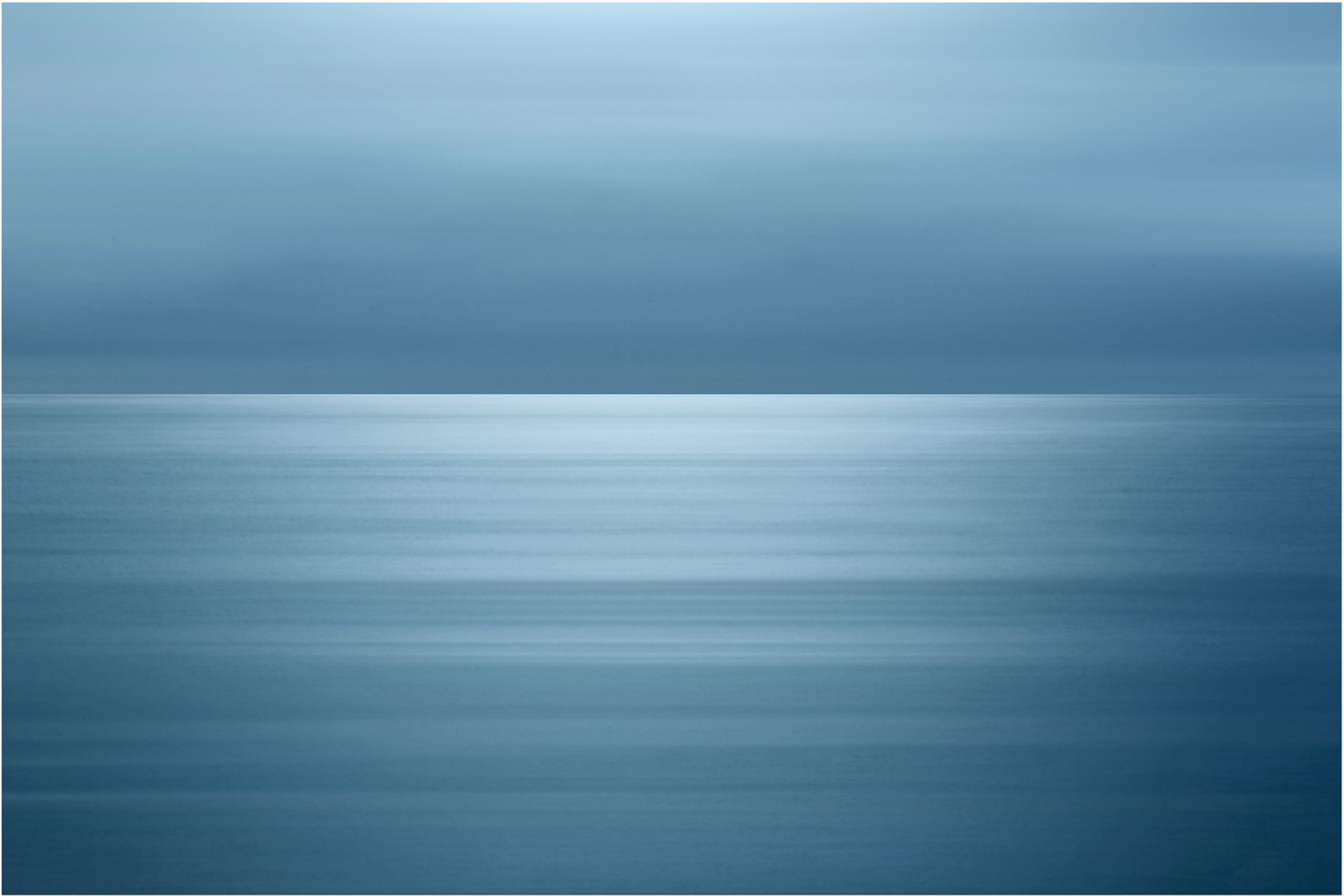

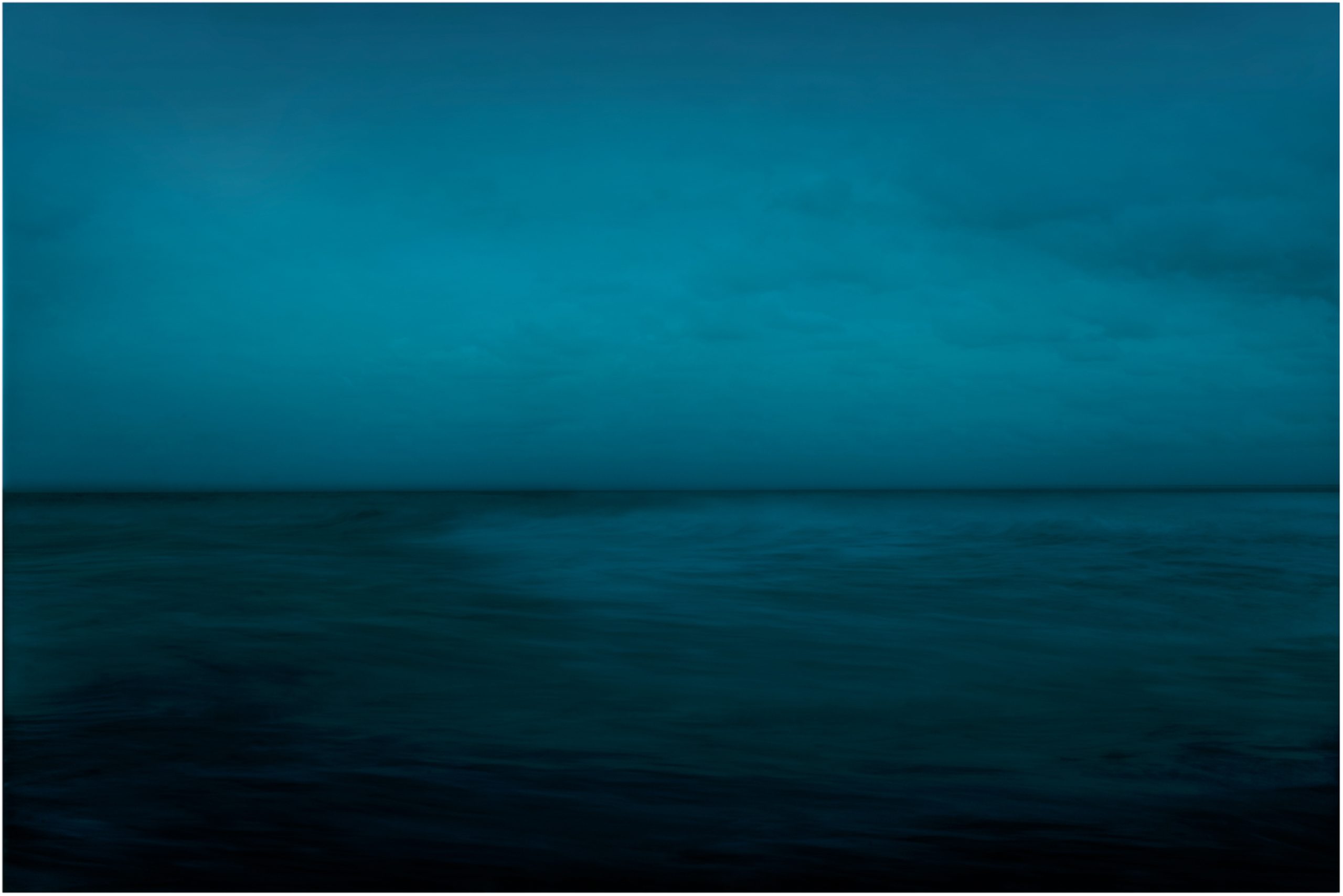

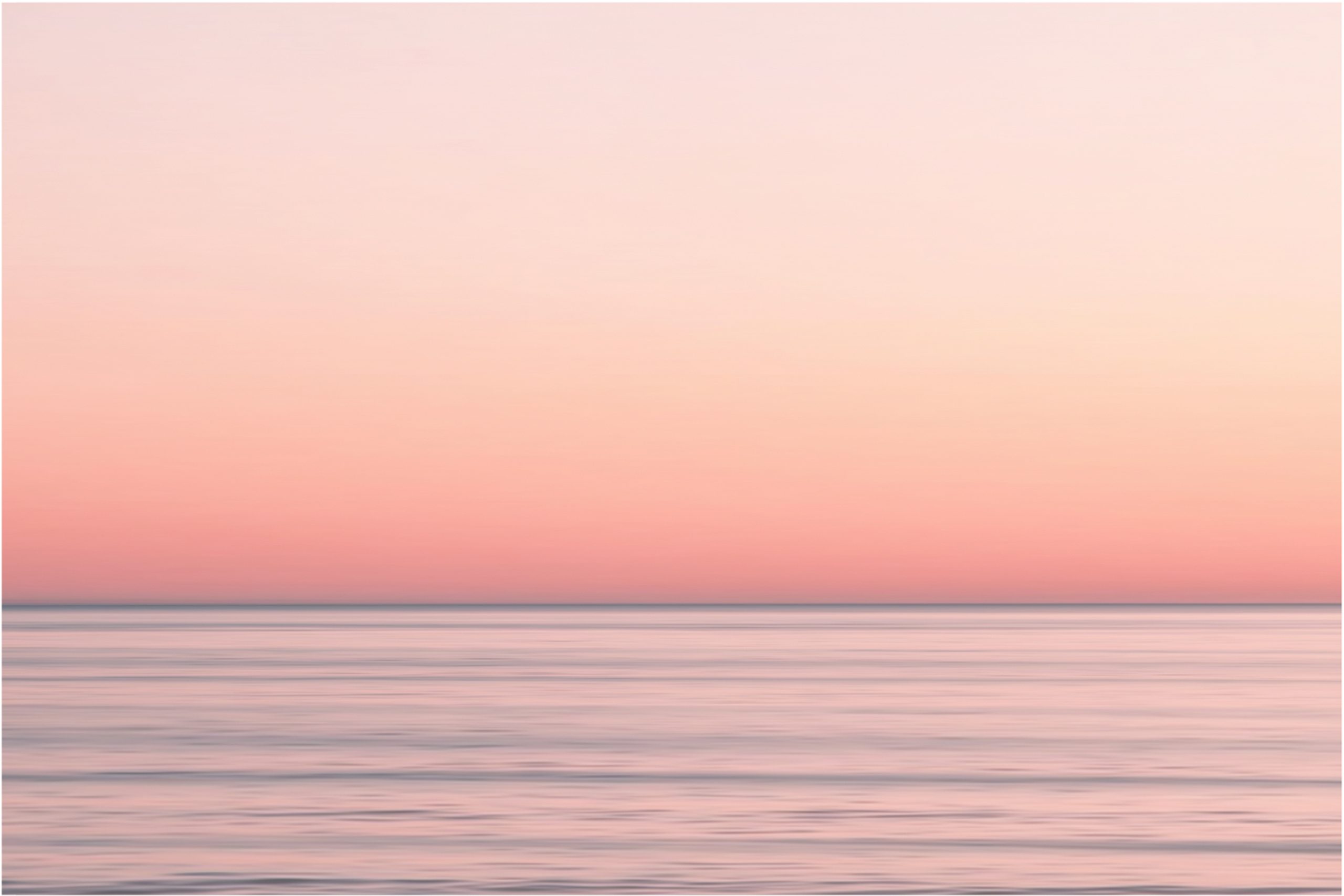

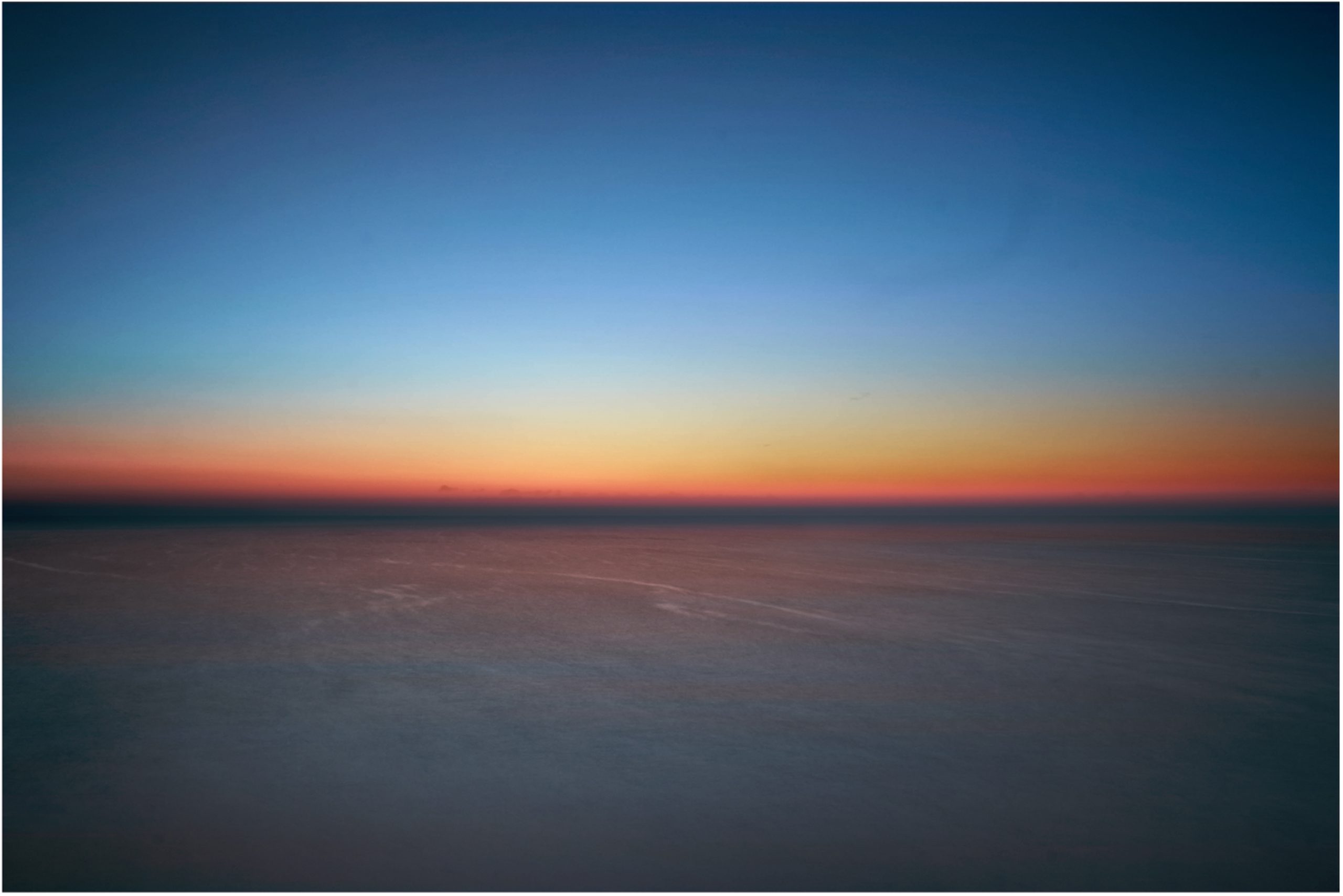

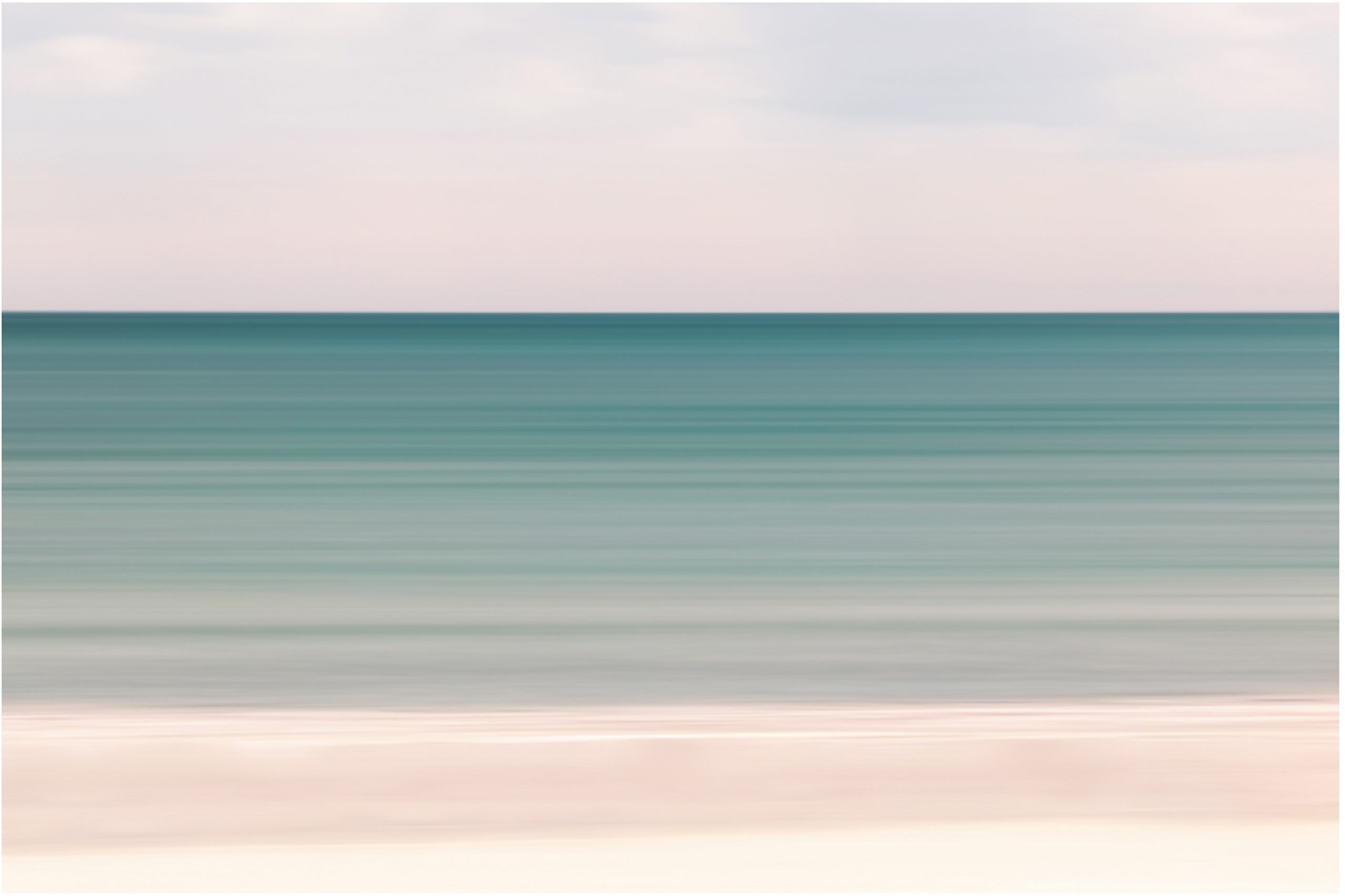

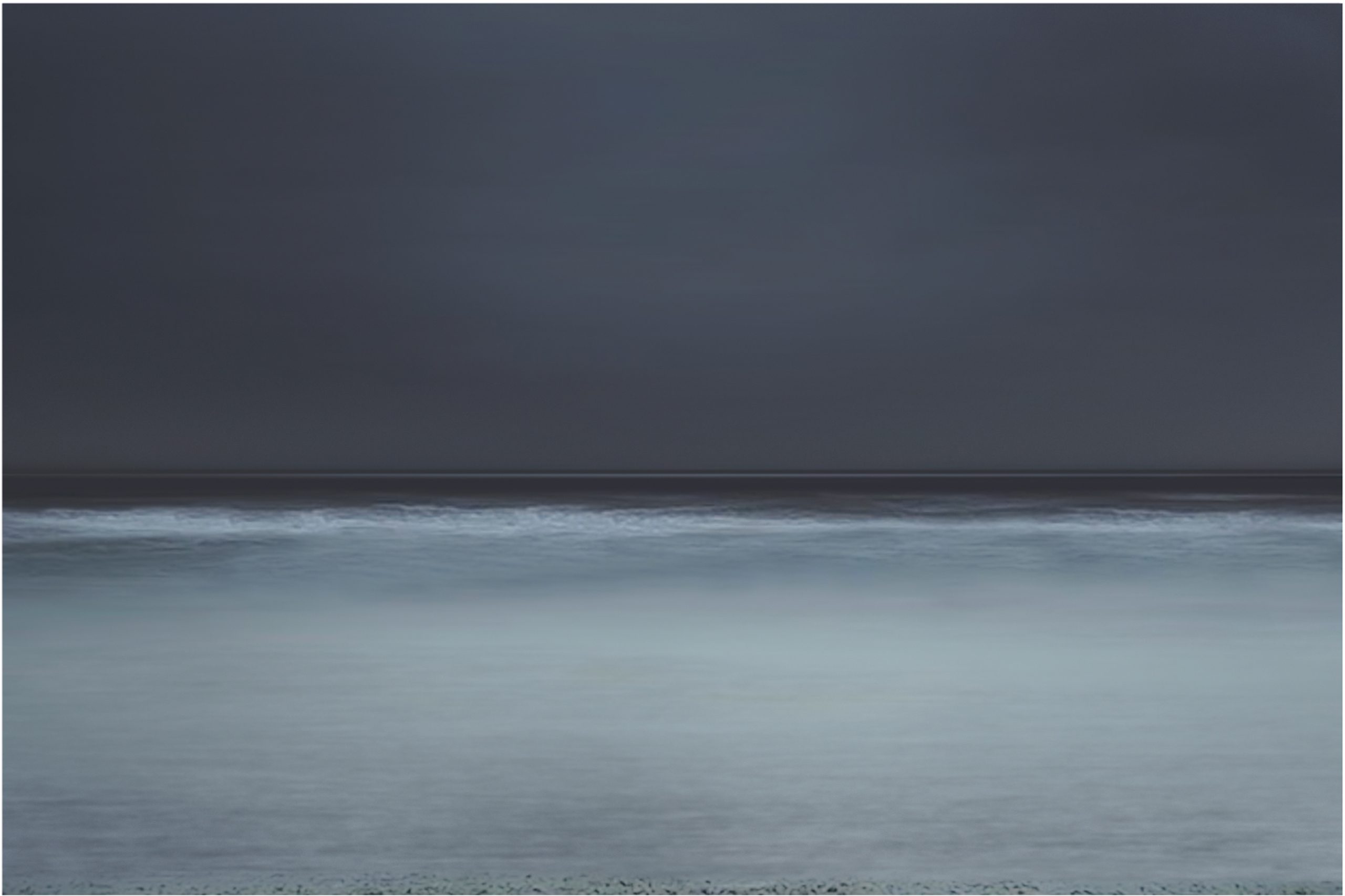

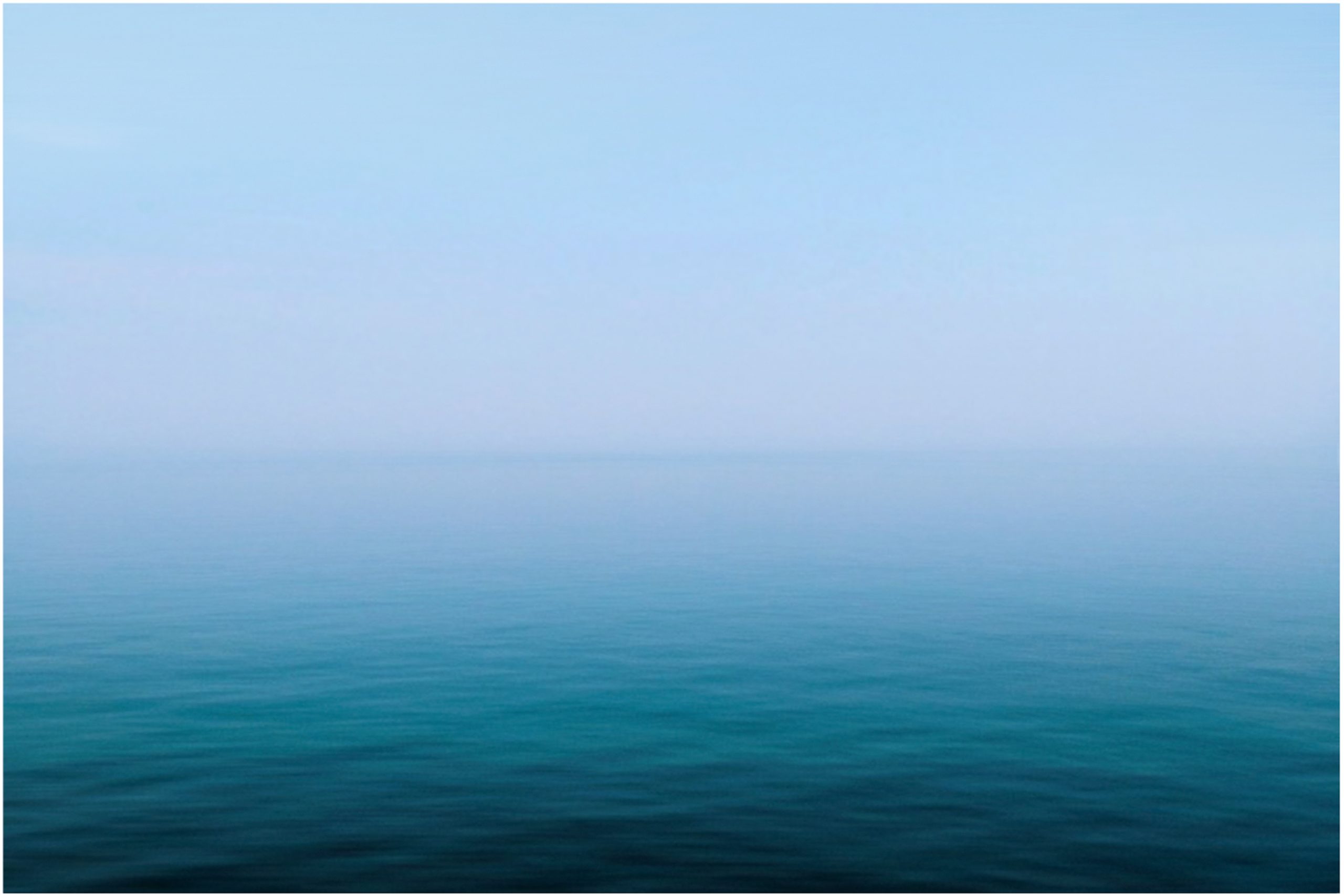

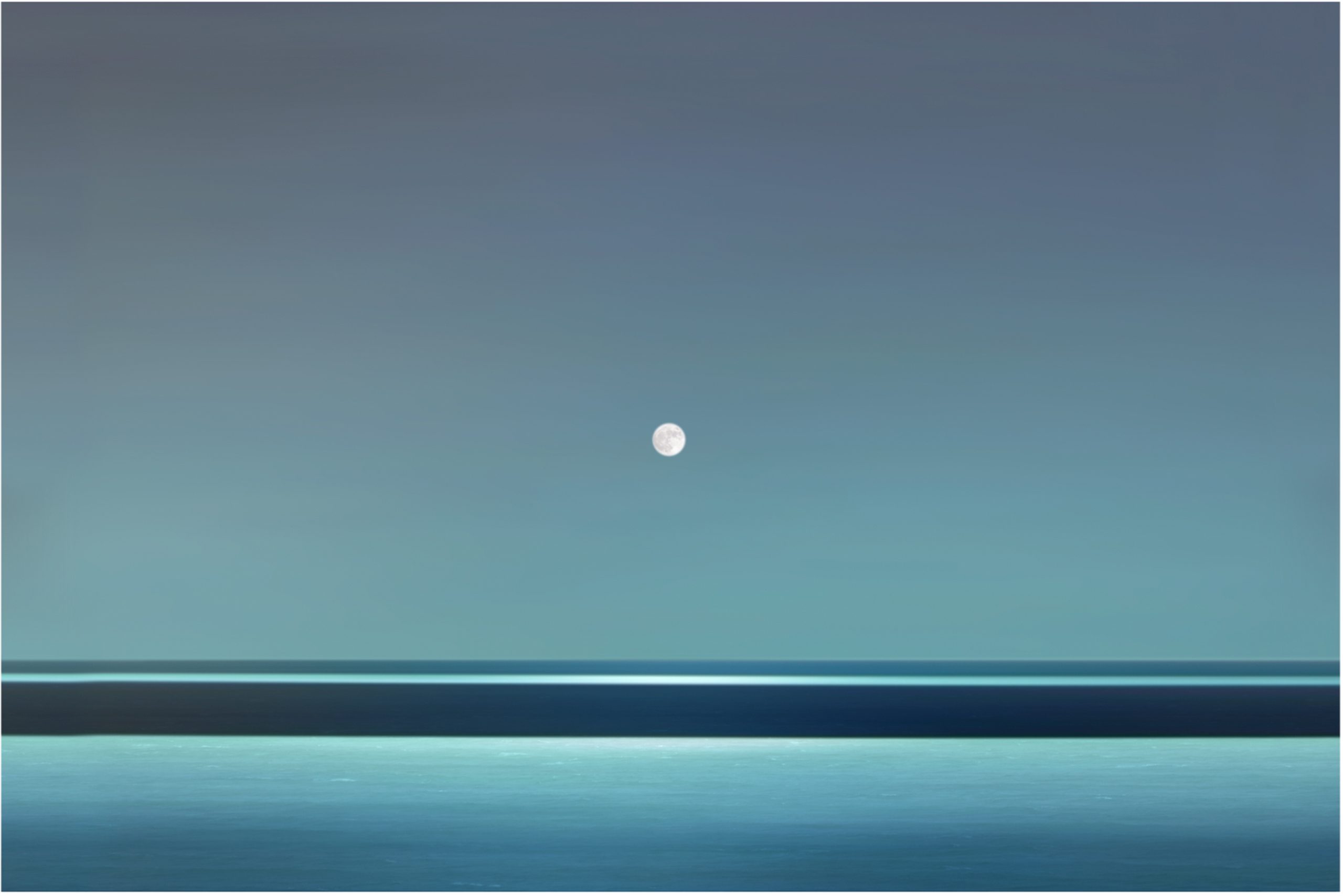

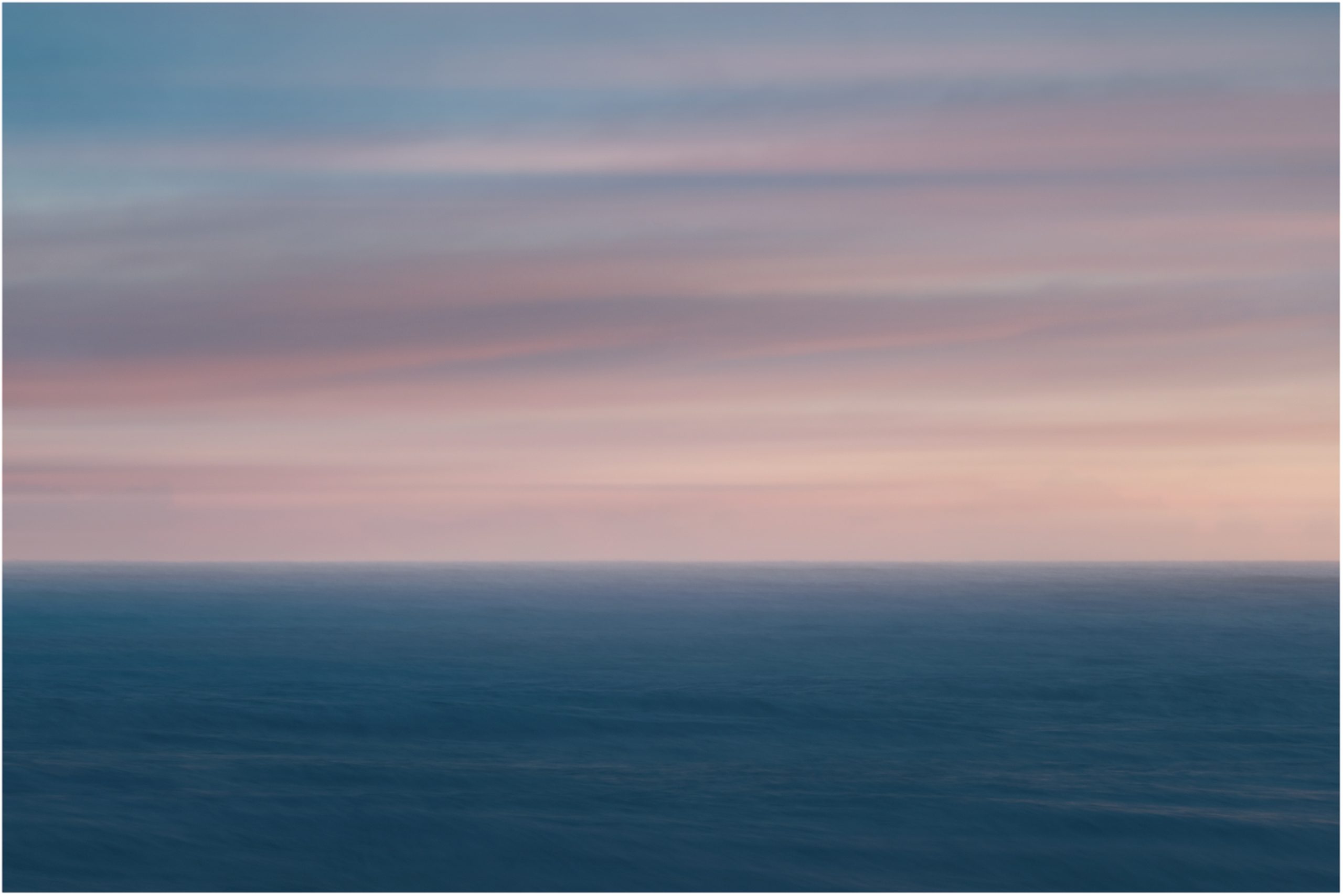

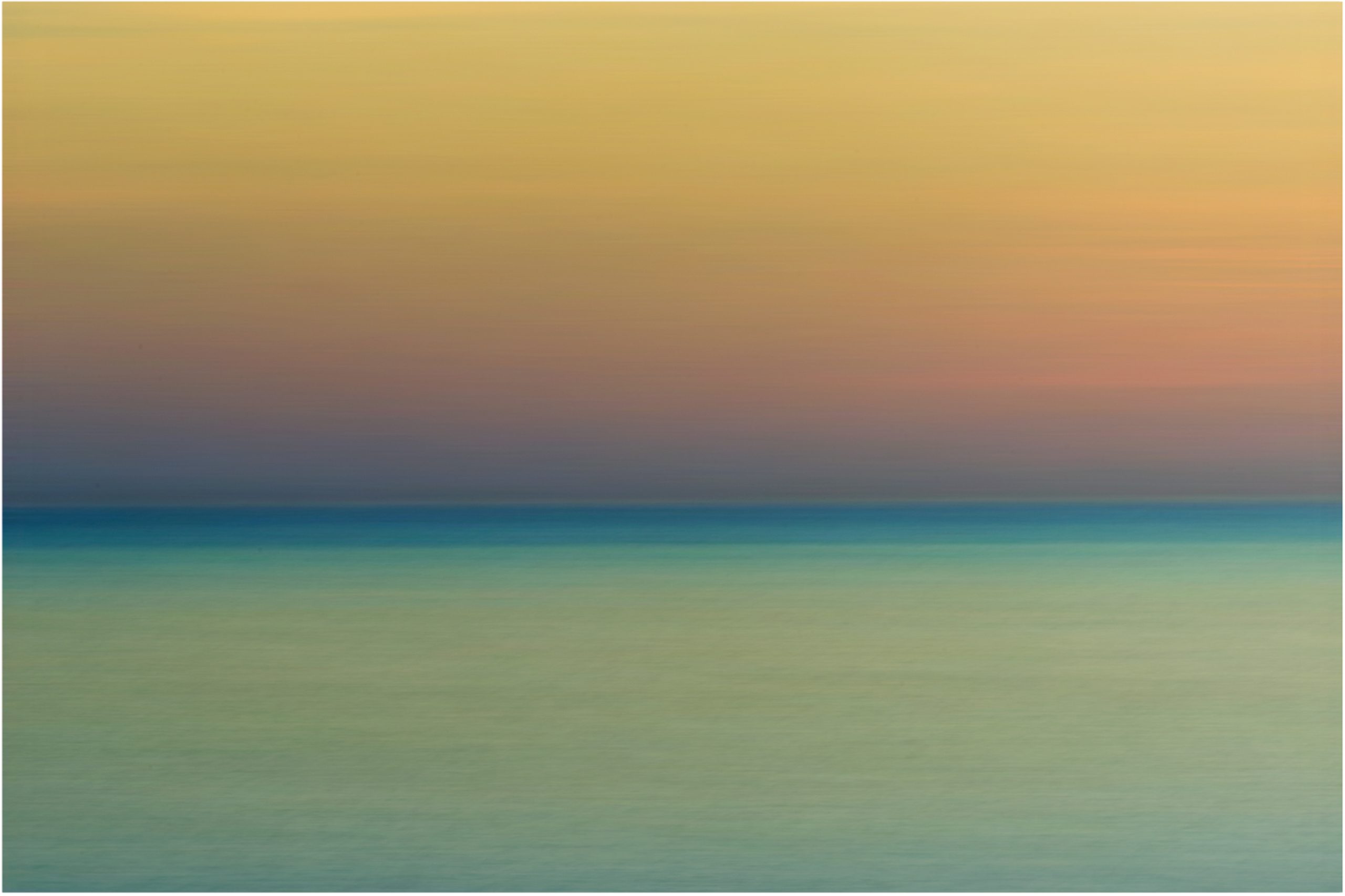

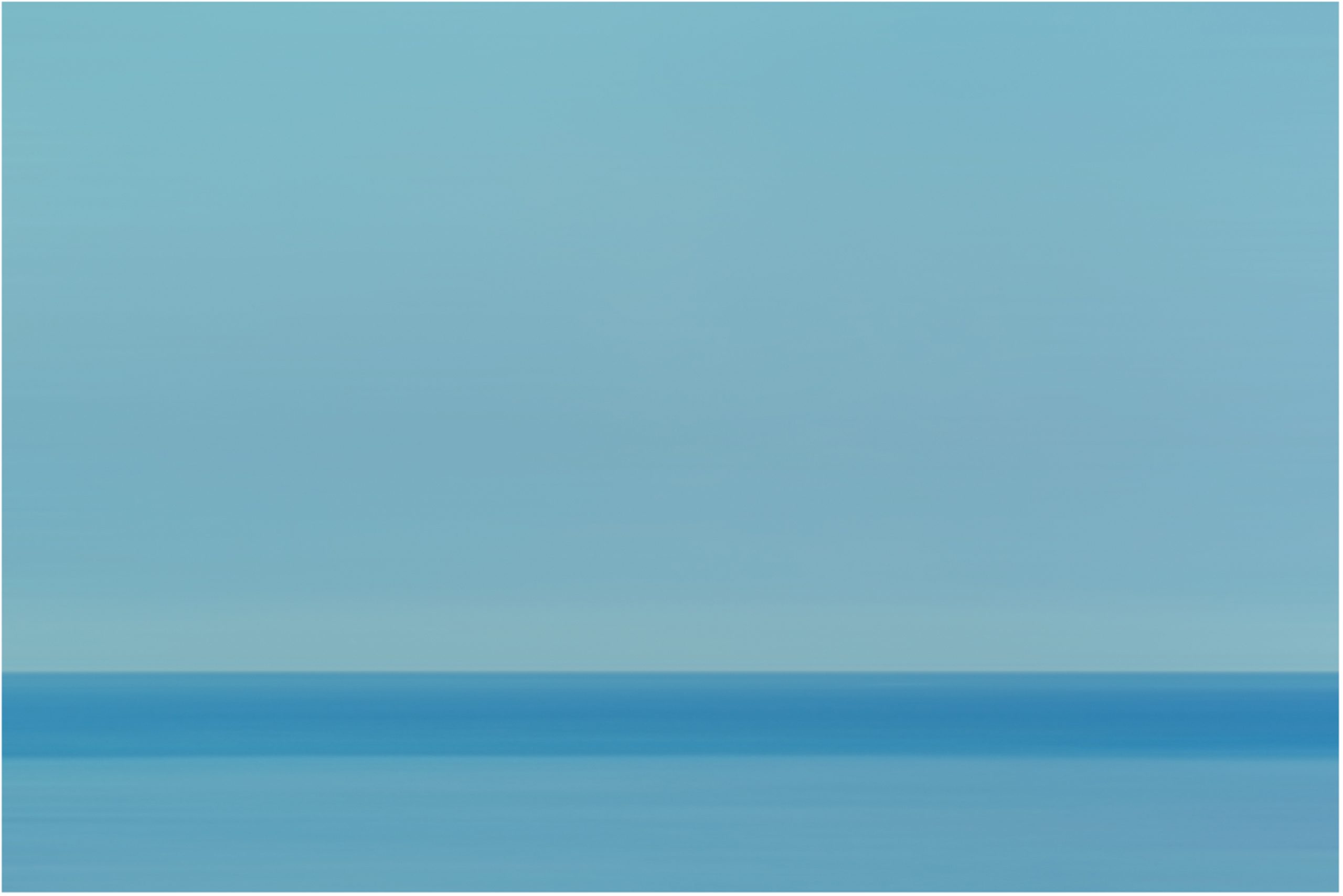

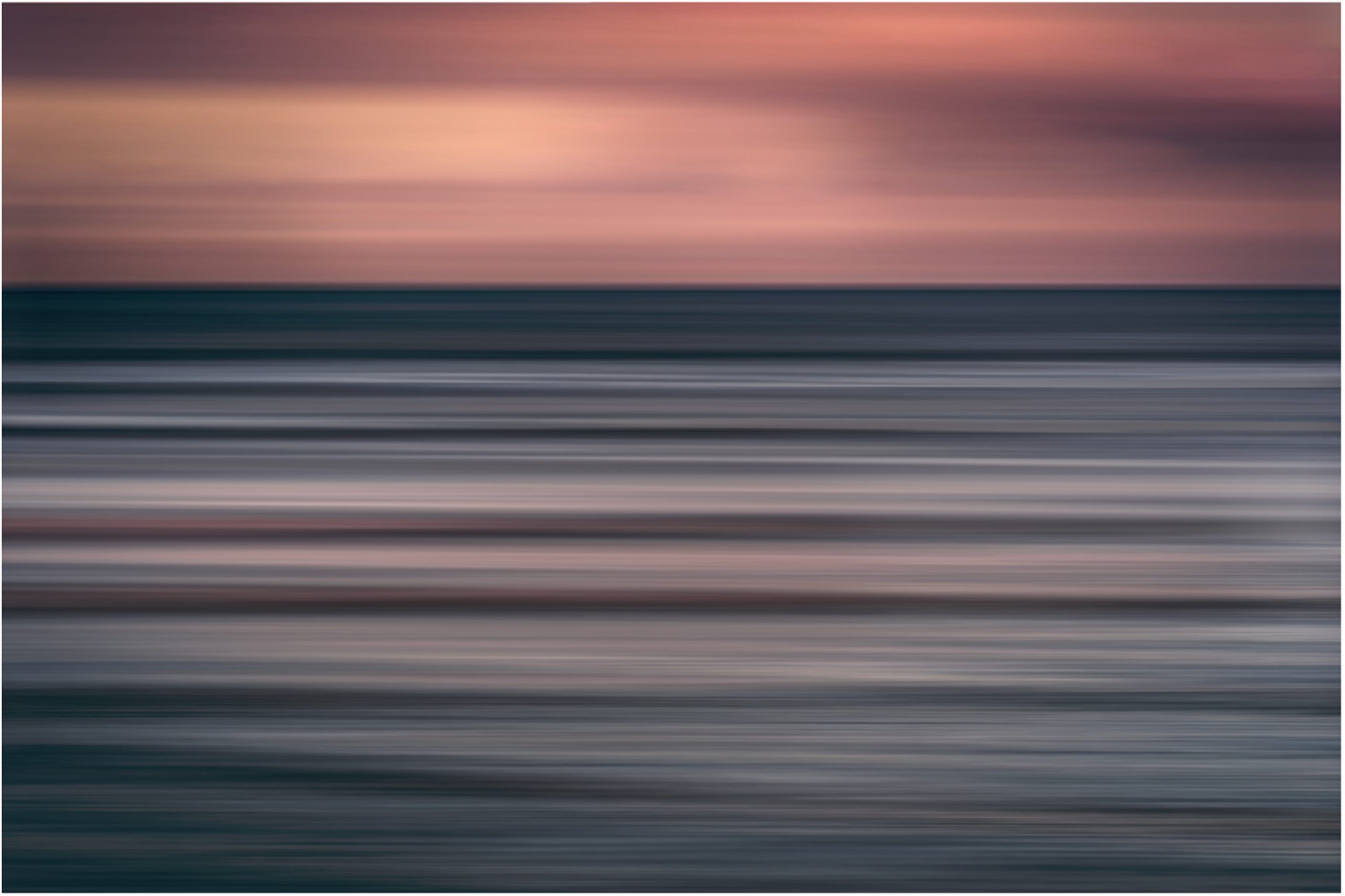

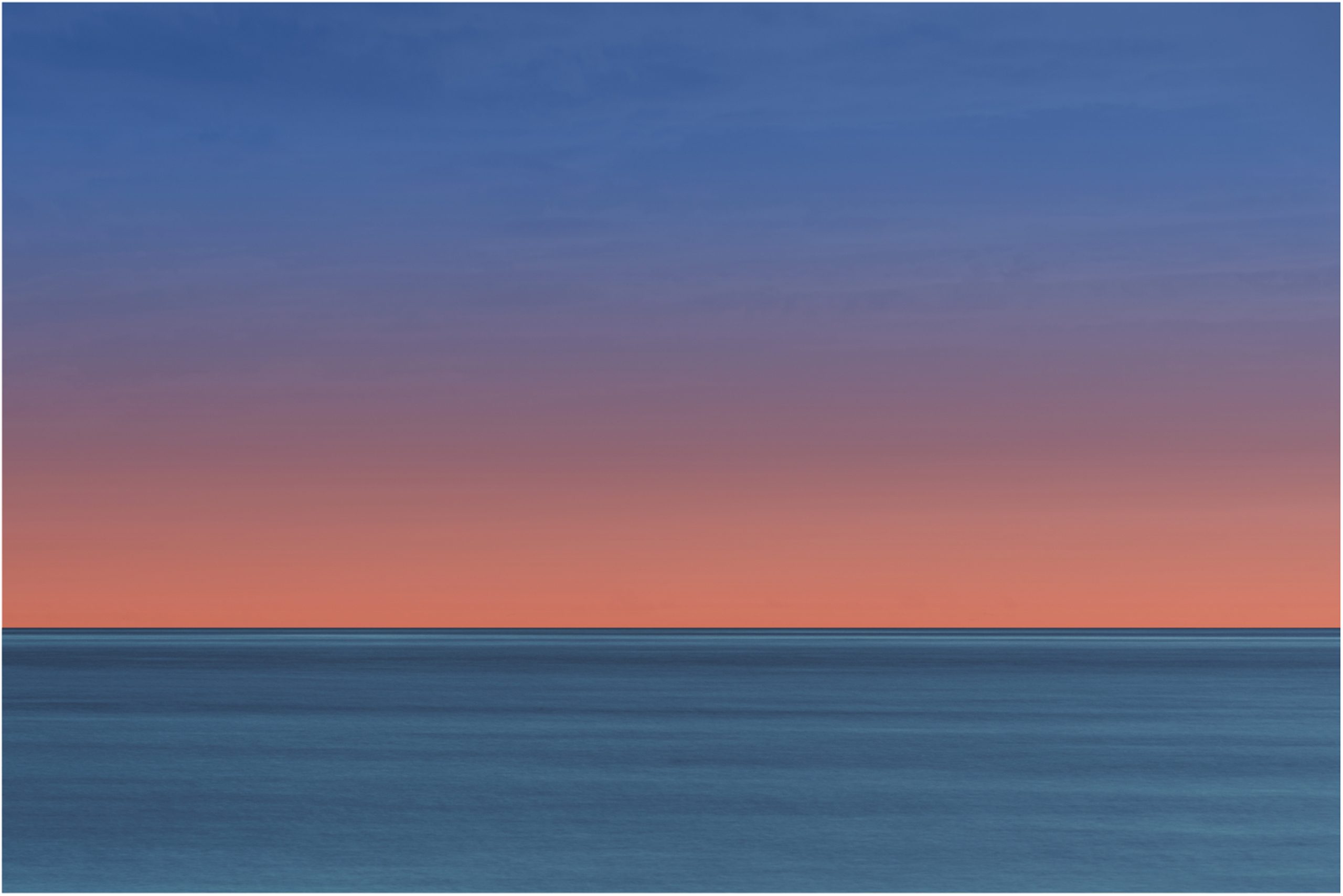

In Late Evening, Wednesday, August 3, 2011, from under an inky mass of clouds, a shaft of light forms a brilliant line on the horizon, breaking cover with a second stroke like a revelation. In Midday, Tuesday, December 17, 2013, high noon has smoothed the waves into a pearly sheen of delicate pastels. The soft pink light of the sky slips effortlessly into pale aquas below, birthing a rainbow. Early Afternoon, Monday, April 2, 2012 showcases a steely chop of waves annihilating the sky and liquifying the horizon, except for a glorious pool of light in the golden section of the composition. Each scene from We are the Weather is singularly absorbing, and encapsulates a moment of transcendence in which the viewer is confronted with the extraordinary, inimitable power of nature. “What do you see here? For me it’s a sheer miracle – light and weather hourly give the landscape new aspects, new moods: the tentative fleeting radiance of dawn and dusk”.

– Andrea Hamilton

Central to Hamilton’s series We Are the Weather is the notion of the sublime. From the Latin sublimis and first outlined in the classical work On The Sublime by an unverified author given the name Dionysus Cassius Longinus, the concept was introduced into Western discourse in William Smith’s 1739 translation of Longinus on the Sublime. [1]Longinus expanded the classical notion of rhetoric (that instructs and delights) to include the idea that art should ‘make one rapturous’ or ‘transcend the mundane’. Etymologically derived from sublimen: “up to a high threshold, uplifted, borne aloft, exalted”,the word suggests an active role in the mind of an audience who complete the effect. It was further elaborated by the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), who enlisted darkness, obscurity, privation, vastness, magnificence, loudness and suddenness into the sublime, which he defined as a kind of pleasurable terror.

A concept both generative and amorphous, the sublime has played a central role in western understanding of art and engaging aesthetic, but also spiritual and ethical values. Longinus suggested the purpose of art was not merely to express the artist’s feelings but to arouse emotion in the audience. He identified this as a loss of rationality or alienation in the viewer which leads to identification with the creative process of the artist and, “A deep emotion mixed in pleasure and exaltation”. The Romantics were enraptured with sublimity; it opened up the possibility of crossings between the self and nature – of transcendence – and expressed the boundlessness of the universe. In Western art of the 18th and 19th centuries, the sublime became synonymous with the immensity or turbulence of nature and our human responses to it, namely that of being over awed – subsumed – by an image. Consequently, sublime landscapes and seascapes of that period featured vertiginous cliffs and chasms, fierce storms, frothing seas, or volcanic eruptions which, if actually experienced, would be life threatening. Many of the works seem to be characterised by a point of illumination, which locate us, “…On the shore/Of the wide world” where, like Keats, “I stand alone and think…”

Curator of Tate show The Sublime (2010), Christine Riding called this, “A pleasurable terror in perceiving objects that might threaten or destroy us”. By contrast, contemporary interpretations of the sublime are underscored by a tacit awareness of nature’s fragility, our impact on it, and the fear of what is being lost. Like Tacita Dean’s Green Ray, or Roni Horn’s Still Water, they simultaneously offer us a glimpse of infinity or momentary oneness with nature, whilst reminding us of its fleeting rarity. With this, they are also posing a question: “What is the sublime?” Is it a thing, a feeling, an event or a state of mind? Moreover, why does it seem such an acutely relevant concept now, in the midst of a global pandemic?

Like seeing our private feelings reflected in a storm, when we experience the sublime in art, we are connected to something greater than ourselves. “Sublimity tears everything up like a whirlwind and exhibits an orator’s whole power in a single blow,” stated Longinus. Unlike other series from Colour of Time, Hamilton’s We Are the Weather isolates the superlative, inimitable and rare moments in which the artist was overawed by what she saw. In seeing these images, we share her pleasure and exaltation. In identifying with her creative process, we also appreciate the fathomless nature of everything – the overlap of history, culture and art – to which she is responding. As the poet Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.”

Precisely because it is so boundless and indescribable, the sublime seems eternally relevant to the subject of water in art. Before the mechanical age this was underscored by our reverence for, and need to survive, the sea. The Wave, by Katsushika Hokusai, pitches a magnificent tsunami against frail wooden boats; in J.M.W. Turner’s Slave Ship (1840), a churning, violent sea leaves a trail of bodies in its wake. Turner alone produced more than 1,000 works on this subject; they embody the liquid depths and gravitational force of the ocean, rife with the dramatic possibility of drowning. This being avoided, within the safe confines of the Royal Academy, the audience experiences a kind of ascendancy: the thrilling relief in perceiving something terrifying that leaves you feeling more alive. For Constable, admiring the beauty of the natural, material world, led on to the idea of a religious and spiritual experience. By the end of the 19th century, advances in scientific and philosophical thinking would dramatically alter our position in relation to the natural world (from powerless to powerful) and with that our understanding of the sublime.

In Renoir’sThe Wave, we can almost see the artist’s brush move through the wet paint. The strokes seem to mirror the action of the wave itself; instead of representation, we have an image of the artist’s emotion in the face of nature. This foreshadowed the seminal Impression, Sunrise, Monet’s masterpiece which gave rise to a whole new genre of art: Impressionism. This shift away from representation was synchronous with the advent of photography, a new medium that would challenge what journalist William Stillman called in 1872, “The affidavits of nature to the facts on which art is based”. The photograph had the potential to capture the random “natural combinations of scenery, exquisite gradation, and effects of sun and shade”. Suddenly, the idea of an artist creating the “effect” of the sublime in response to nature was interrupted. One might say there was a transference of terror at this point in the history of the genre of landscape art (and subsequently the definition of the sublime), from the subject to the object of our creations.

Here we come to Gustave Le Gray, who created one of the most poetic and technically impressive early photographs of the ocean: The Great Wave. From a series of landscape works (1855-1856) that banished all narrative, their effect was so powerful on contemporary audiences, they seemed to usher in a new era of the sublime. In 1857, a critic for the Journal of the Photographic Society effusively described them: “A gush of liquid light, full and flush on the sea, where it leaves a glow of glory… it is as if Jacob’s Ladder of Angels was just withdrawn…” Le Gray would come to be considered the first fine-art photographer; his works have a universal quality that makes them awe-inspiring today. Whilst a passing gleam of light might well have led to biblical associations in other times, today our sense of wonder is compounded by a yearning for communion with nature itself. These photographs inspired new works of art like Arthur Rimbaud’s poem “Elle est retrouvée. Quoi? – L’Eternité. C’est la mer allée Avec le soleil…” and would have a profound effect on generations of artists.

The technical brilliance of Le Gray’s image is especially resonant. Le Gray used the Wet-collodion process, but wanted his images to mirror what the eye sees versus what the camera captures. He had to find a way to marry the compact movement of waves with the diffuse light of the sky, which needed different exposure times. So he took two images and then combined the negatives, fusing them on the horizon line. Like Turner, in this way Le Gray heightened the dramatic effect of this epic, unbroken prairie of open sea, vaulted and trenched with waves dancing in the light… and we see the artist’s vision.

Longinus believed that sublime works of art ‘could model a soul’, and ‘that a soul could pour itself into a work of art’. It is this feeling which is manifest in Hamilton’s We Are the Weather. A celestial ellipse of light that forms over the dark fraught waves in Early Morning, Saturday, April 12, 2014, seems to call forth the soft peach light above the horizon in spite of the looming presence of clouds. There is the echo of Horn’s words in Still Water: “Water is a spiritual presence, in the company of water I feel the presence of things that exceed me.” Just like Turner and Le Gray, Hamilton went out in search of the sublime. Within a strict conceptual and technically rigorous framework she created the conditions for its momentary capture.

We are the Weather opens a flow of associations in the viewer’s mind, such as Gerhard Richter’s Seestuck, 1969, a masterwork of photorealism. Like Le Gray, Richter referenced two unrelated images of a sea and sky to create this painting. Of particular note are the countless tonal adjustments which manipulate the spectator’s focus, as if he was using his paintbrush like a lens. Hamilton’s images capture the sublime salty air and hazy atmosphere of Richter’s open water, and we are reminded that photography and its evolution is entwined with the landscape of contemporary art.[2]

As Longinus said, the mind has to be prepared to perceive the sublime, and its effect is a collaboration between the artist and the viewer. We depend on the artist to make that happen in the work, as if they are making the weather. Just as Le Gray took two separate images and fused them into a sublime whole, Hamilton takes all her accumulated memories of this genre and invests them into each piece. These works reflect acontemporary awareness of climate change and how this has altered our relationship with the ocean – not just of its impact on us, but our impact on it. Further, in reference to the sublime, Hamilton considers how the ocean has mediated our relationship to the history of art and ideas. When she photographs an empty expanse of sea and sky in Rothko washes of slate blues and greys, she is referencing a lineage that encompasses both the luminosity of Gustave Le Gray‘s atmospheric photographic seascapes of the 1850s and the saturation of Abstract Expressionist paintings of the 1950s. We are the Weather is a reminder that whilst our experience in this world is singular, it is also something shared.

Nico Kos Earle

NOTES:

[1] The author is unknown. In the 10th-century reference manuscript (Parisinus Graecus 2036), the heading reports “Dionysius or Longinus”, an ascription by the medieval copyist that was misread as “by Dionysius Longinus.” When the manuscript was being prepared for printed publication, the work was initially attributed to Cassius Longinus (c. 213–273 AD).

[2] Plotinus (204–270 A.D.) brought idealism to the Roman Empire as Neoplatonism, and with it the concept that not only do all existents emanate from a “primary essence” but that the mind plays an active role in shaping or ordering the objects of perception, rather than passively receiving empirical data. If early photographers had no option but to negotiate their own engagement with painting, their modern descendants can call on nearly two centuries of photographic history. What the photograph taught us is that perceptions of the sublime in the external landscape are shaped by cultural experiences. With so many images of so many extraordinary places seen but not experienced, how do we then experience reality? What can an artist do to bring that essential response back for the viewer?

THE APPRECIATION OF THE REAL

Laura Vallés

Editor of Concreta art journal

Life as a journey

Water has played a crucial role in the work of Andrea Hamilton, whether as a backdrop to the narrative or the main focus of her body of work. Perhaps water has even been the vehicle for her work, as the best way to consider the oeuvre of Andrea Hamilton is to think of it as voyage, an adventure story, a tale of obstacles, encounters and wonders. This journey is, of course, not yet at its end. Indeed, just the opposite.

One of the most famous and influential voyages in literature is Homer’s Odyssey. This epic poem opens in the middle of the story and the expedition is recounted in the in medias res (in the midst

of things) narrative technique. Flashbacks, conveniently placed storytellers and other devices are used to fill in the gaps of earlier events. This literary and artistic technique has been employed by many novelists and artists such as William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf and Andy Warhol to name a few, and is a standard element of film noir.

Like the water for Hamilton, this story leads us to two different ideas or patterns around the body of work of this artist, these are, the creation of a project in medias res and the notion of voyage. I like to think of Andrea Hamilton’s modus operandi as akin to this form of narration, this way of creating a project, which directly recalls a human memory, a memory that collapses time, a memory understood as a non-linear narrative, a memory that condenses its spatial forms and its premonitory structures.1

Over the past two decades Hamilton has gathered together twenty years of analogue and digital imagery in several archives organised chronologically: an astonishing family album –worthy of mention and of another essay– merged with thousands of images of seascapes, land scenes and water works from around the world, from Alaska to South America, and from Iceland to Africa. This archive is full of document, but also abstraction, reality and metaphor and it certainly works as a creative turning point for the artist.

The second idea pointed out by Homer’s inspirational verse refers to the notion of journey. Having examined the artist’s archive on several occasions, what I glimpsed from the experience of looking

at two decades of the artist’s life and recurrent trips between the UK and the US (among other escapades) is that her ethnographic approach to her subjects of interest, based on observation and desire to know, poses important questions full of curiosity about human influence on the natural world. In this regard, Andrea Hamilton could be described as a traveller, a sort of anthropologist understood as Joseph Kosuth described in his article ‘The Artist as Anthropologist’ in which he explained:

‘For the artist, obtaining cultural fluency is a dialectical process which, simply put, consists of attempting to affect the culture while he (or she) is simultaneously learning from and seeking the acceptance of the same culture which is affecting him (or her).’ 2

Ultimately, seeing is learning, and hence sharing.

REVERIES OF THE TIMELESS SEA

‘You can’t date the sea. It’s timeless.’ 3

On this particular occasion, Hamilton presents two bodies of water-based work. The first one is called Tidal Resonance and is metaphorically compared by the artist to a very short form of Japanese poetry called ‘haiku’ – previously called ‘hokku’–, a seventeen-syllable poem often represented by the juxtaposition of two described images or ideas and a cutting word between them. The second one is Luminous Icescapes and it is composed by a series of photographs presented as a sequence of precious gemstones.

The rough sea, Extending toward Sado Isle, The Milky Way.

In 1689 the author of this poem, Matsue Basho ̄, one of the most renowned writers in the Japanese Edo period, started a long (and also ethnographic) trip full of inquisitiveness to the Pacific coast

in which he ended up admiring the scenic beauty of Mutsushima and the island of Sado, and writing one of his most celebrated short pieces. In Western society J. D. Salinger, whose verses were published in 1953 by The New Yorker magazine, popularized haiku poems. Nowadays, even The New York Times shares this serendipitous poetry.

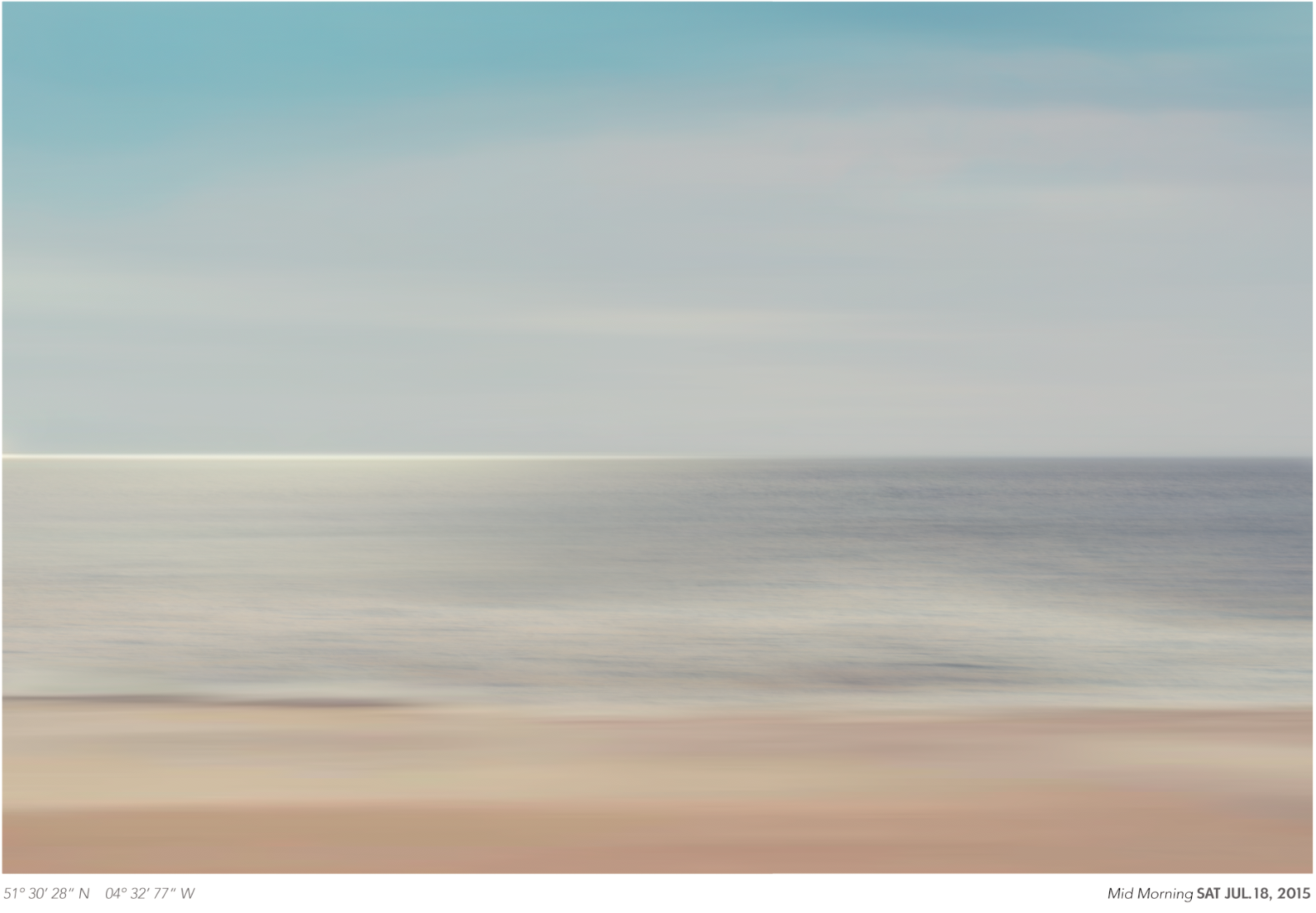

The strong presence of the sea in Japanese culture, especially in the haiku poems of Basho ̄ , appealed to Andrea Hamilton who developed a series of seascapes in Florida, following the echoes of these lines and their power to evoke images, provoke impressions, memories or traces in the spectator’s minds. The cultural importance which the sea has had in our history – both in Western and Non-western societies and in our imagination, covers a wide spectrum of possibilities. The ocean is the territory of the sublime, the mysterious and the unknown. And, judging by recent events, this remains true even after the appearance of satellite geo-positioning devices and the broadening of the imagination through literature and art. 4

Japanese tradition and landscape have also inspired other creators such as, for instance, English artist Hamish Fulton or Canadian- American painter Agnes Martin. Fulton’s artistic practice starts by making an actual delineated walk in a particular location and then by producing artworks that refer to it. For Fulton this experience of the landscape is about engagement, where the rhythm of the walk meets the land. It could be considered as a form of meditation transformed into art. His photographs with text don’t document

an action or an encounter the way photography documented early Performance and Body Art from the 1960s and 1970s, or the way photography was used to record Land Art or Earthworks such as Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) or Richard Long’s A Line Made by Walking (1967); on the contrary his photo-texts invite the viewer to surpass the document, suggesting an idea of the felt incident. The walking artist provides basic information on the duration, location and conditions of these walks to Haiku-like passages from his diaries.

On the other hand, Agnes Martin’s paintings, akin to Andrea Hamilton’s photographs in this idea of interpreting the poems delicately and visually, are intimate abstract representations of ‘what is known forever in the mind’ and not ‘about what is seen.’ 5

Even though she considered herself an abstract expressionist, her style was eventually defined by an emphasis upon lines, grids and fields of pale washed colours. For this reason – apart from the obvious lack of figurative references in her paintings – Martin’s oeuvre was hung in several exhibitions along with other works by minimal artists such as Sol LeWitt or Donald Judd. This idea of writing without letters, or writing with colour and form, can be observed in canvases such as Untitled (1959) or Gratitude (2011).

This mode of submerged haiku-esque narrative operates as well

in Andrea Hamilton’s Tidal Resonance, composed of a series of photographs shot in Vero Beach that depict the movements of water and waves. These photographs of the ocean cannot help but suggest Sigmund Freud’s oceanic feeling of limitlessness, the sensation of an indissoluble bond, as of being connected with the external world in its integral form. 6

The immensity of the sea is framed in these pages, some of them intimate and quietly represented, and some others furious and blurred; some of them full of colours, some others with a pale washed tone. The horizon plays the role of the haiku’s cutting word

between two images; occasionally depicted closer to the Great Wave Off of Kanagawa, intermittently akin to a Sugimoto’s time-lapse. The horizon divides, breaks and cracks the scene in two with a delimited line, as if it were the stripe made by Fulton in one of his maps, or the bar painted by Martin in one of her canvases. Yet, more than once this line disappears and a feeling of loss prevails due to the lack of reference.

In the second body of work developed in Iceland and Alaska, Hamilton depicts a different scene of tension, which has its own kind of pictorial energy. Luminous Icescapes opens up another pictorial possibility at the same time that emphasises the complex issue of climate change.

There is a new growing ethical consciousness within the arts relating to a series of art practices that implies a greater receptivity for the environment we live in. Instead of bringing a dozen pieces of blue-tinged ice into the art space like Olafur Eliasson did in his immersive and criticized installation Your Waste of Time at MoMA PS1 in New York last year, Hamilton did not interfere with the habitat. On the contrary the artist depicted a sequence of crystalline structures, ‘the solitaire jewels of nature that we need to preserve in order to safeguard Arctic environment for the future.’ 7

Tidal Resonance and Luminous Icescapes are a multi-layered palette of complex feelings and emotions. They range from mysterious, cautious, secretive and brave representations of the water and the ice, to empowered, serene, elegant or relieved

depictions of waves and sparkles. Perhaps these bodies of work can be interpreted as a portrait of the artist, always fleeting, in continuous movement. At some level, this notion would follow the idea described by Sally Mann in which she assumed that

‘every image is in some way a “portrait”, not in the way that it would reproduce the traits of a person, but in that it pulls and draws (this is the semantic and etymological sense of the word), in that it extracts something, an intimacy, a force.’ 8

In other words, these seascapes and icescapes metaphorically associated with poetry and ecology reveal the artist’s perception of her leitmotiv, the water, and ultimately her own impression capable of concealing hidden worlds.

1 In One Way Street, Susan Sontag’s introduction describes the role of memory, time and space in Benjamin’s writings and explains how the author could write about himself more directly when he started from memories. Walter Benjamin et al.,

One Way Street, London: Verso Classics, 1997.

2 Joseph Kosuth, ‘The Artist as Anthropologist’ (1975), The Everyday: Documents of Contemporary Art, edited by

Stephen Johnstone, Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2008.

3 Cited in Royoux, Jean-Christophe, Cosmograms of the Present Tense, In Tacita Dean, Tacita Dean, London:

Phaidon Press Limited, 2006, p. 89.

4 On March 8, 2014 a Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 went missing less than an hour after takeoff. The largest search and rescue effort in history is still failing to locate the plane. None of the photographed objects by various countries’ satellites has been confirmed as belonging to the missing aircraft. A few months later it is still a mystery.

5 An interview with Agnes Martin by Chuck Smith and Sono Kuwayama at her studio in Taos in November 1997.

See: http://vimeo.com/7127385, (last accessed on 15 August 2014).

6 Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, trans. James Strachey, New York and London: Norton, 1961, pp. 11-21.

7 See Andrea Hamilton Online: http://www.andreahamilton.com/Luminous- Icescapes-2013-14, (last accessed on 15 August 2014).

8 Cited in Joseph J. Tanke and Colin McQuillan, ‘Jean-Luc Nancy, The Image – the Distinct’, in The Bloomsbury Anthology of Aesthetics, Bloomsbury Academic, 2012, p. 505.