Celestial Black | Source: How colour takes us on a journey

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense

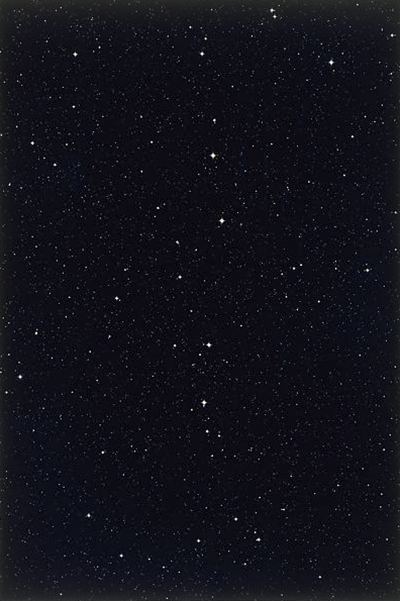

Milky way in night sky, 2004 © Ron Miller

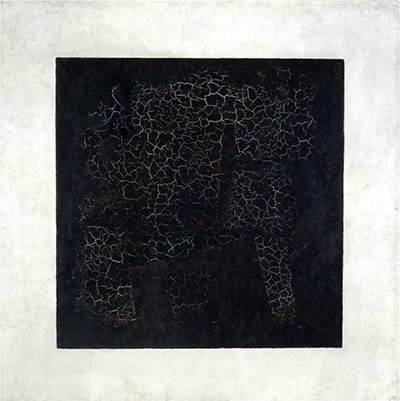

Space might encompass the deepest black but it is lit by the delicate pinpricks of moons and planets, spinning in the dark emptiness, infinitely wondrous to the curious mind. Our own beautiful satellite is under observation at the moment as NASA has been celebrating Apollo 11’s first landing on the Moon 50 years ago and is preparing to send another ship to the Moon in 2024 called Project Artemis. We are reminded that space tests the limits of our knowledge and our capacity for technology … and one colour might hold the key: celestial black. We call celestial black, that black you find in space that suggests the infinite. It is a mysterious black as we don’t know what lies beyond. Until recently, we have only been able to approximate the utter darkness of space in paint. True black, the absence of light, was represented with dull pigments. Artists relied on their imaginative power to conceptually express what the material could not. The Kiev-born painter Kasimir Malevich, founder of the Suprematist movement, created Black Square in 1915, widely considered the first purely abstract painting.

Black Square, 1915, Kasimir Malevich © Public domain

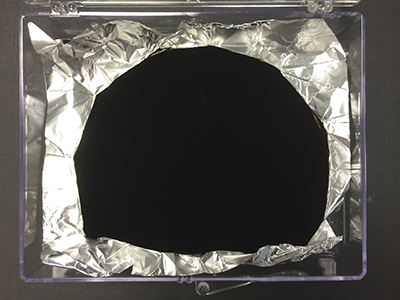

In 2014, Ben Jensen working with British company Surrey NanoSystems, created a new material as groundbreaking as the discovery of ultramarine blue during the Renaissance: Vantablack. Standing for vertically aligned carbon nano tube arrays, it is one of the darkest substances ever created. The coating, which absorbs virtually all light, was developed to eliminate reflection in satellites and telescopes. Refined in 2016, it is a substance whose blackness is unmeasurable by a spectrometer. Not technically a pigment, if you were to look at it through a microscope you would see a dense forest of carbon nanotubes that act as a molecular trap for light: photons glide seamlessly into the material, but cannot escape – like an alternative, microscopic universe, energy held in potentia. Might this be the closest humans can come to creating a black hole?

Vantablack coating, 2014 © Surrey NanoSystems

While initially developed for astronomers, it was the art world who first communicated the explosive impact of this new discovery to the rest of us. Anish Kapoor was so enamoured with Vantablack, he bought exclusive rights to its use, which precipitated an ongoing battle with the artist Stuart Semple. It raises questions about ownership of something as important and universal as colour: how can anything so magnificent belong to anyone? How can one artist reserve the rights to a material with so much potential?

Descension, 2015 © Anish Kapoor

Vantablack has a myriad of applications from coating stealth aircraft for near invisibility to enhancing the very thing we use to look deep into space: the telescope. Almost entirely non reflective, it has the capacity to prevent stray light from entering telescopes. It seems the best way to see deep into space is by being in the colour of space itself, under a blanket of complete darkness… like closing your eyes.

It is not the first time innovation in one discipline has profoundly influenced another. Indeed, as The Colour Project has shown with Mauve and Chrome Yellow, it is often the accidental discovery of colour that acts as a catalyst for exciting new works of art (think of Van Gogh’s glorious Sunflowers). Vantablack allows us to experience a total absence of light equivalent to being in space, and brings us face to face with the mystery of space itself: infinity. This non-colour lies at the heart of many of the greatest narratives about intergalactic travel from Star Wars, A Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, and 2001: A Space Odyssey to The Little Prince. If true black represents the infinite, it is also full of possibility; the kind of darkness that leads to self-revelation.

“And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

― The Fox in The Little Prince, 1943

The Moon, 2019 © Andrew McCarthy

So why does space have no colour? Essentially it is empty. The daytime sky is blue because light from our sun hits molecules in the Earth’s atmosphere and scatters off in all directions. The blue colour of the sky is a result of this scattering process. At night space looks black because the Sun is on the other side of the planet and there is no nearby bright source of light to be scattered. Why do we see this dark blanket and not brightly-lit stars? Why doesn’t the light from all of them add up to make the whole sky bright all the time? Olbers’ Paradox refers to the apparent contradiction between our expectation that the night sky be bright and our experience that it is black.

However, if you are on the Moon, which has no atmosphere, the sky is black both night and day. You can see this in photographs taken during the Apollo 11 Moon landing on July 20, 1969.

One of the questions a celestial black raises is the idea of time travel, as all planetary bodies are placed in relation to one another. “Space is a form of coordination of coexisting objects and states of matter It consists in the fact that objects are extraposed to one another (alongside, beside, beneath, above, within, behind, in front, etc.) and have certain quantitative relationships. The order of coexistence of these objects and their states forms the structure of space.” (Source. A. Spirkin, Dialectical Materialism.)

This brings us back into the forest of nano tubes that trap the light in Vantablack. By creating this material, scientists have succeeded in approximating the conditions in outer space, that will allow them to see further than was ever thought possible. The question is, if the light has vanished, what will they see? Indeed, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright once said: “Space is the breath of art.” In this context, space can be positive or negative, open or closed, shallow or deep, two-dimensional or three-dimensional. Sometimes space isn’t explicitly presented within a piece, but the illusion is given.

Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery‘s 2015 exhibition Space Age consisted of work from artists seeking to process the sometimes unbearable magnitude of space. In it, the painter and sculptor Robert Longo depicts the Russian astronaut Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space. The show, confirmed that presently we are still seeking to represent space, and that the pictures sent back from these distant horizons are still the main source of artistic inspiration – most notably William Anders’ image Earthrise.

While no human has returned to the Moon since Apollo 17 left its surface in 1972, artists continue to go there imaginatively. Opening this week at the National Maritime Museum, London, The Moon celebrates the 1969 landing of Apollo 11. It features more than 180 extraordinary objects, including rarely-seen pastels by the prominent 18th-century Royal Academician John Russell. Melanie Vandenbrouck, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich describes her awe: “By night, he spent 20 years of his life sketching the Moon. This devotion resulted in a group of exquisite lunar ‘portraits’… This view conveys the thrill of seeing, through the telescope, a world emerging from a deep blue ether.” Vandenbrouck was also a judge for the Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2018.

Night Sky #16, 2000–2001, Vija Celmins, collection SFMOMA © Vija Celmins; photo: courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Many artists continue to be inspired by found images of space, such as Lithuanian-born artist Vija Celmins. Celmins moved to the US as a child and taught herself English, reading comic books that celebrated the dawning of the era of space exploration, stating: “It just takes a second for all the information [in the comic] to go in, then you can explore it later”. Her meticulously-detailed drawings, paintings and sculptures from found images are perfect microcosms that each take years to complete: “Through the making you take millions of decisions, and this gives the work a personal identity… a presence.” (interview by Tate Artists Studios, Painting Takes Just a Second to go in). Her works make powerful connections between distant objects, highlighting the interconnectedness of all things, like the ocean and the Moon. While taking pictures of the ocean in the 1960s, satellites captured images of the Moon’s surface. Attracted by their range of silvery greys, she amassed a large personal archive, on which she based a number of drawings, such as Moon Surface (Luna 9) No.1, 1969. Like her ocean drawings, they faithfully document any camera distortion, glare or blurriness and pay particular attention to negative space. Via these drawings she locates herself within this expanding universe.

Night Sky 3, 2002 is a charcoal drawing on paper that depicts an expanse of night sky, almost photorealist in its detailed depiction. Some of the stars are blurred whilst others are hyper-real, creating a shimmering depth of space and infinity. It is one of the many night-sky studies Celmins has made across a range of media:

“I tend to do images over and over again because each one has a different tone, slant, a different relationship to the plane, and so a different meaning. The meaning for other people tends to be a projection of their own romance.” (interviewed with Chuck Close, 1991.)

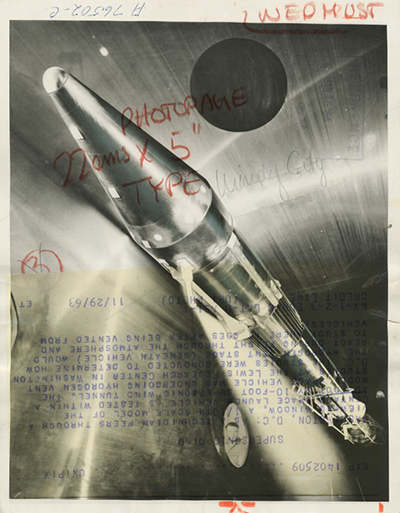

Stars, 05h, 08m/-45 degrees, 1990, Thomas Ruff © Artists Rights Society, New York

More recently, the artist Thomas Ruff has been using found images from the NASA archive, blowing up and often distorting pictures such as archival star-scales from a Chilean observatory for Sterne, NASA photos of planets for Cassini. “I wanted to make super-sharp, really precise photographs of the starry sky, but quite soon I realized that even though I was professionally educated and professionally equipped, I was not able to take those photographs by myself. I needed the help of an observatory with a big telescope. For the first time, I had to give up authorship to create these images.”

During this process, Ruff has also returned to making unique images with photograms, a camera-less technique of working with photosensitive paper used by Man Ray and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Abstract in nature with lines and spirals, these seemingly random formations echo Ruff’s intuitive notion of the fundamental structures of the universe: “The world is abstract. Take a look at the scientific photographs of atomic particles colliding taken at CERN in Geneva.” In his work, we see the duality of being and nothingness, order and chaos, sparked by moments of deep human connection found in the making of each work.

press++01.55, 2016 © Thomas Ruff

Why is it that the things dearest to us have the most meaning when furthest away? Does travelling into darkness lead to the brightest of revelations? Perhaps, like the earth we are standing on, it is impossible to see things properly when we are in them. Only distance provides the kind of perspective required to see something in its entirety – like the Moon in the night sky. For so long, we wanted to reach it but when we were finally standing on the Moon, it was the Earth – a beautiful blue marble in the pitch black – that captivated us.

The earth and the moon from 10^8 km, 2016 © RON MILLER

As our planet increasingly crumbles under the combined weight of everything we have created on it to create our increasingly complex civilisation, it is understandable that there is a movement to look outwardly. But is studying and trying to portray space a futile idea? One only has to look outside on a starry night to be confronted by the sheer size of it. And the fact that humans are so afraid of introspection that they must move to larger ideas is an age-old artistic and personal conflict. Why are we trying to learn about the world ‘out there’, when we know so little about the world around us, and ‘in here’?

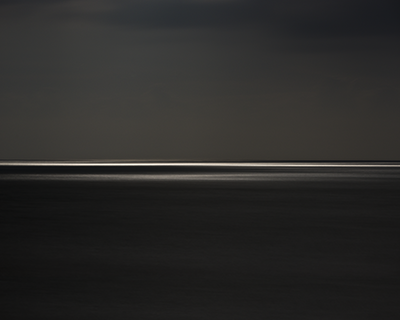

Sea of Celestial Black, 2014 © Andrea Hamilton

“We (humans) are in the flow of the cosmos because we, like the planets, all life and the Universe are one”

― Carmel Garan

Milky Way, 1990 © Peter Doig

Explore Further

Exhibitions:

19 July 2019 – 5 January 2020: The Moon, National Maritime Museum, London.

To 25 March 2019: 50 Years from Tranquility Base, National Air And Space Museum In Washington, USA.

13 April – 2 Sept 2019: Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission, The Museum of Flight, Seattle, USA.

To 5 January 2020: Museum of the Moon, Luke Jerram, Natural History Museum, London.

11 May – 17 November 2019: From Madrid to the Moon, Espacio Fundación Telefónica, Madrid, Spain.

3 April – 22 July 2019: La Lune, Grand Palais. Paris, France.

29 June 2019 – January 2020: Apollo 11 Exhibition, Powerhouse Museum, Australia.

20 July – 16 September 2019: Apollo 11: The Eagle Has Landed National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation, Tokyo.

7 August: The Sound of Space: Sci-Fi Film Music, BBC Proms. Royal Albert Hall, London. Broadcast on Radio 4 on 9 August.

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense