Classic Blue | Connections: How colour interacts with the wider world

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense

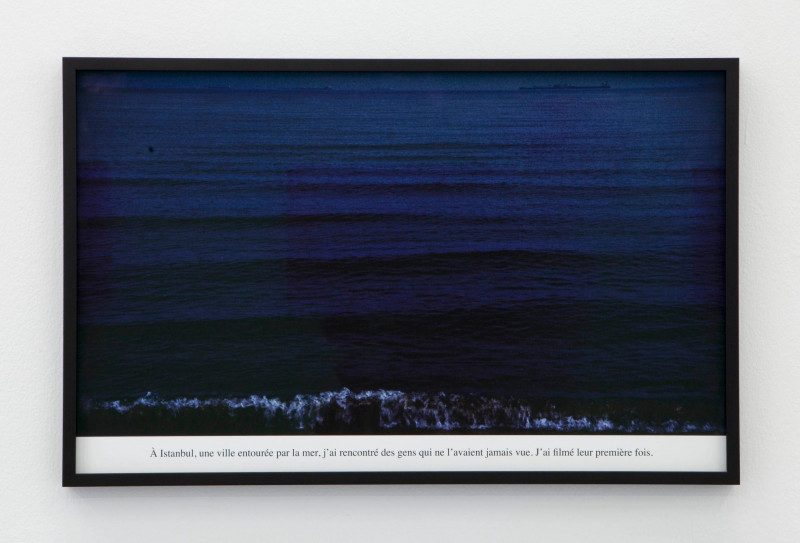

Sophie Calle, Voir la Mer, 2011. Courtesy Perrotin

“They came to the water’s edge, separately, eyes lowered, closed or masked. I was behind them. I asked them to look out to the sea and then to turn back towards me, to show me eyes that had just seen the sea for the first time.” – Excerpt from Voir la Mer, Sophie Calle, 2011.

At home in Paris, the celebrated artist Sophie Calle (winner of the British Photographic Society’s Centenary Medal in 2019) read a newspaper article about a suburb in Istanbul where many of the inhabitants were so poor they had never travelled; and despite their proximity to the Bosporus, had never seen the sea. Calle went to Turkey to meet them and take them to the ocean. “I took 15 people of all ages, from kids to a man in his 80s… once we were safely by the sea, I instructed them to take away their hands and look at it. Then, when they were ready – for some it was five minutes and for others 15 – they had to turn to me and let me look at those eyes that had just seen the sea.” The project resulted in 14 five-minute videos, created by Caroline Champetier, with each subject filmed from behind, and eventually turning to face the camera. The audience becomes witness to the raw power of emotion when confronted by something so mighty. We see a face changed by what they have seen, and we share their emotion.

Sophie Calle, Voir la Mer, 2011. Courtesy Perrotin

Many of Calle’s projects stem from these almost voyeuristic impulses, and incorporate moving images, photography, direction and text. She blurs the boundaries between reality and fiction, life and art, to set up an unveiling of reality — her work reminds us that what limits our perception is more often a lack of opportunity or imagination than anything else… and reverses the cliché, ‘out of sight, out of mind’.

Whilst many of us have seen the ocean, very few of us have been to or even heard of the high seas. The furthest, largest part of the ocean, 63% of its body, they lie 200 miles offshore and beyond any national jurisdiction. Expert marine biologists say that in addition to a wealth of marine life and complex ecosystems, the high seas play a key role in regulating the earth’s climate, by driving the ocean’s biological pump that captures huge amounts of carbon at the surface and stores it in the oceans’ depths. Without this process, they warn, the atmosphere would contain 50% more carbon dioxide and become too hot to support human life. As the legendary oceanographer Sylvia Earle told DIVE magazine: “Once we stop killing all the tuna, the swordfish, the sharks, the grouper and all the other fish on an industrial scale, there is a chance that the pattern of appalling destruction I have seen in my life can become a time of recovery”.

BLue Marine Foundation

A healthy ocean not only sequesters carbon dioxide, it creates more than half the oxygen we breathe – which means every second breath we take comes from the sea. Blue Marine Foundation (BLUE) is a charity dedicated to restoring the ocean to health by addressing overfishing, one of the world’s biggest environmental problems. BLUE’s mission is to see 30% of the world’s oceans under protection by 2030. Scientists, conservationists, campaigners and politicians are stepping closer to this vital aim, now listed at #14 in the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. A team of academics has released a detailed plan of how we could link up a global chain of vast marine reserves across previously unprotected international waters. “The speed at which the high seas have been depleted of some of their most spectacular and iconic wildlife has taken the world by surprise,” said the co-author of key research, Professor Callum Roberts from the University of York.

To bring this story to life, and provide a vital emotional connection with this abstract, distant area of water, AH Studios collaborated with BLUE and 36 artists with a special interest in the seas, to create a show that revealed not just its strength as a perceptual concept, but also a real place; bringing the easily overlooked into the public realm so its importance can be seen. (How much do we want to say here?)

BLUE SHOW IMAGE

Meanwhile , the underwater photographer Philip Hamilton has just completed a series of short films entitled Ocean Souls for the new media company UPROAR. Each of the five episodes gives voice to one aspect of life under the waves, seen through the eyes of cetaceans: emotions, language, social organisation, intelligence, and human interaction. This last is key, as the film is not meant to anthropomorphise dolphins and whales, but show their extraordinary range of experience and why they are so important to life on earth.

“We believe that science and beauty can touch public opinion. It is harder to kill a whale or a dolphin that has emotions, suffers, has a name and a family. Rather than using shocking images and create controversy, we will use science, fun and beauty with the hope of triggering change. Our goal is to show the intelligence, social behaviour and strong feelings of the animals, supported by science and complemented by beauty.”

– Philip Hamilton and Clément Perette

Humans came from the sea: whales and dolphins returned to it, some 50 million years ago. They understand deep blue better than anything on the planet. Their intelligence is not in doubt: they not only have the largest but also the most complex brains in the animal kingdom. Their social organisation and language skills are second to none, and in many aspects can challenge ours. They recognise and name individuals, and pass the mirror test so easily that we could think they are vain (as well as curious). They solve problems better than any other non-human animal, and communicate across thousands of miles. No cetacean is a threat to humans: even the apex predator in the aquatic environment, the so-called killer whale, has never been reported attacking a human in the wild. They do not deplete the ocean fish-stock; the largest ones eat the smallest animals, krill and plankton. Despite all this some developed countries hunt them for meat: rich nations that have no particular need for that protein and could find easily economic means to replace the proceeds of the hunt.

Philip Hamilton and sperm whale, © Bougie Geographic

Whilst there is a huge amount of work to be done, by identifying the problem, and giving a voice not only to its victims but showing why this matters to us as a species, we can begin to see a way forward… and seeing is believing.

Philip Hamilton, Call of the Blue

Source | Connections | Physis | Sense